Levi Conant House, 330 Harvard Street, Cambridge, MA – façade [Courtesy of Christopher Hail and Cambridge Historical Commission]

Notable Elements

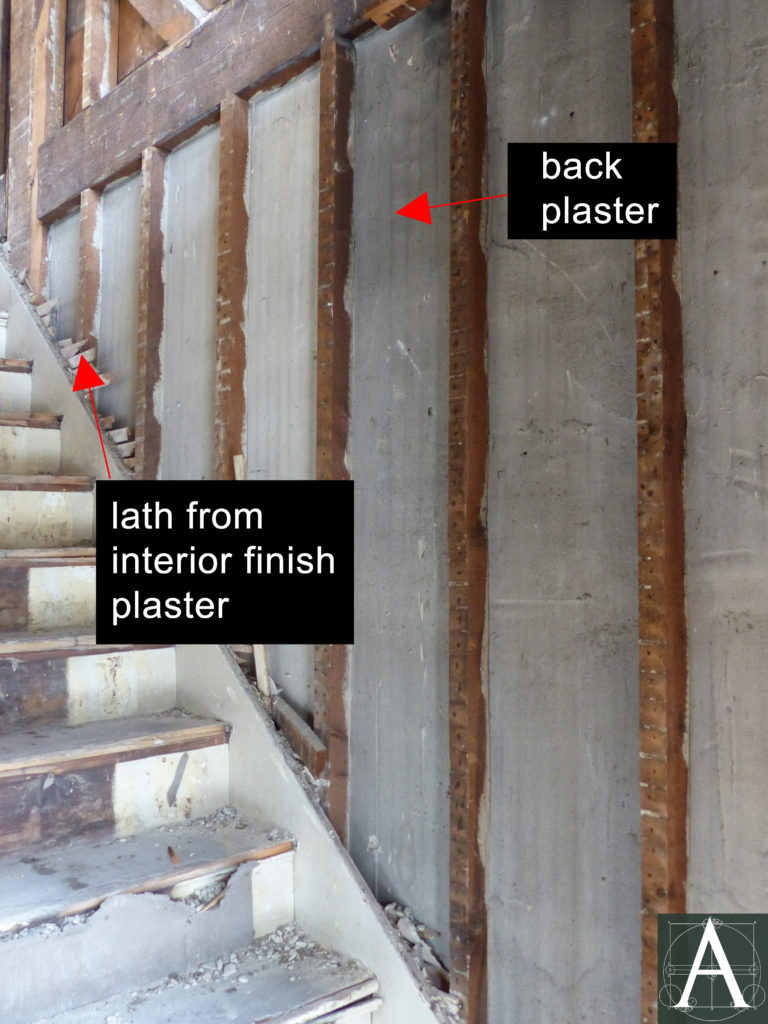

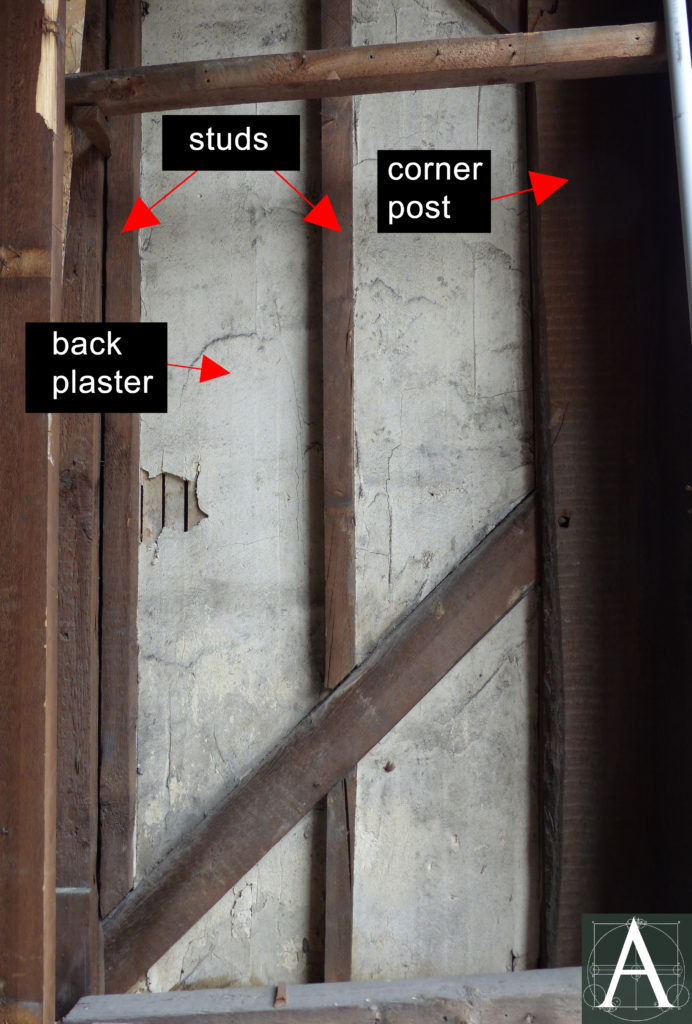

- Back-plaster throughout first & second storeys [Interior]

- Surviving building contract [History]

- Deed restrictions (1835) on the use of the property [History]

- Plumbing installation from ca. 1861 (lead lines) [History]

- Braced-frame construction [Frame]

- Octagonal cupola [Exterior]

History

Built in 1844, the Levi Conant House typifies the types of well-built, middle-class houses constructed in the early suburban development of Cambridge. The house stands on a parcel composed of three lots created as part of a subdivision of the estate of Judge Dana by Alexander Wadsworth, Surveyor, on October 19, 1835. Lots were conveyed subject to detailed restrictions governing the setbacks of buildings from the street and uses permitted on the property. Restrictions warned that if the owner:

shall suffer any building to stand or be erected within fifteen feet of either of the streets bounding said lot or shall use or follow or suffer any person to use or follow upon any part thereof the business of a Taverner Carpenter Cabinet maker Cordwainer Butcher Currier Soap boiler Brewer Distiller Tallow Chandler Sugar Baker Brazier Tinman Dyer Founder Smith Brickmaker or any nauseous or offensive business whatever then…a Proprietor of any lot of land represented upon said plan shall have the right after sixty days notice thereof to enter upon the premises with his servants and forcibly if necessary to remove therefrom any building or buildings standing within fifteen feet of either of the Streets aforesaid and every thing appertaining [sic.] to any of said Trades …herein referred to… [Middlesex County Registry of Deeds, Book 346, pages 414-415 – Deed with Building Restrictions for 330 Harvard Street]

Preceding the era of suburban expansion that followed the construction of railroad lines in the 1840s and 1850s, such restrictions represented new notions of suburban town planning and the protection of residential districts in the 1830s. Development of the parcels may have been slowed by the Panic of 1836, as it was not until 1844 that the property was purchased by Levi Conant (1801-1873), a merchant from Charlestown, who engaged William Hovey Junior, architect to design a new house.

William Hovey (1810-unknown) was a native of Massachusetts who conducted an architectural practice from the 1830s until ca. 1856 when he moved to Michigan where he owned and managed “valuable gypsum mines and a $35,000 Victorian architectural plaster production facility…near and in Grand Rapids, Michigan where he also worked to build and to design a 19th century Baptist Church.” [unpublished email notes dated April 22, 2015 from John Goff to Samantha Paull in the files of the Cambridge Historical Commission, Cambridge, Massachusetts] Designing in the Greek Revival and subsequent romantic Victorian styles, Hovey worked with Calvin Ryder as a junior partner during the early 1850s. Hovey had a large practice in Cambridge where thirty-four of his commissions are documented in Cambridge building records [William Hovey Junior – identified buildings in Cambridge, MA] compiled from local newspapers, tax records, deeds, street directories and other sources.

Less documentary exists for William H. Hayden and Thomas H Megroth who were listed as carpenters in the Cambridge directories of the 1840s. Working in loose partnership, Hayden and Megroth were constructing two other houses in Cambridge at the same time that the Conant House was under construction (50 Inman Street and 43 Pleasant Street).

A building contract for the Conant House was executed on July 1, 1844 [Building Contract for 330 Harvard Street], the terms of which required completion of the house by December 1, 1844 for a total cost of $4,400 to be paid in installments:

Five hundred dollars when the stable is put up and trimmings on and slated and the cellar of the house finished, five hundred dollars when the buildings are raised and boarded, eight hundred dollars when the house is ready for plastering, and one thousand dollars when the house is plastered and outside finished, eight hundred dollars when the inside is all finished, except painting and papering, and the balance of eight hundred dollars when the work is all completed according to plans and specifications. [Middlesex Registry of Deeds, Book 445, pages 488-489.]

Although the contract does not describe individual architectural details, it does state that the stable’s roof was to be covered with slate. It is likely that the house’s roof was also slated. In addition, one of the contract’s scheduled payments was to be made when the interior was finished “except painting and papering” revealing that lime plaster walls were originally wallpapered.

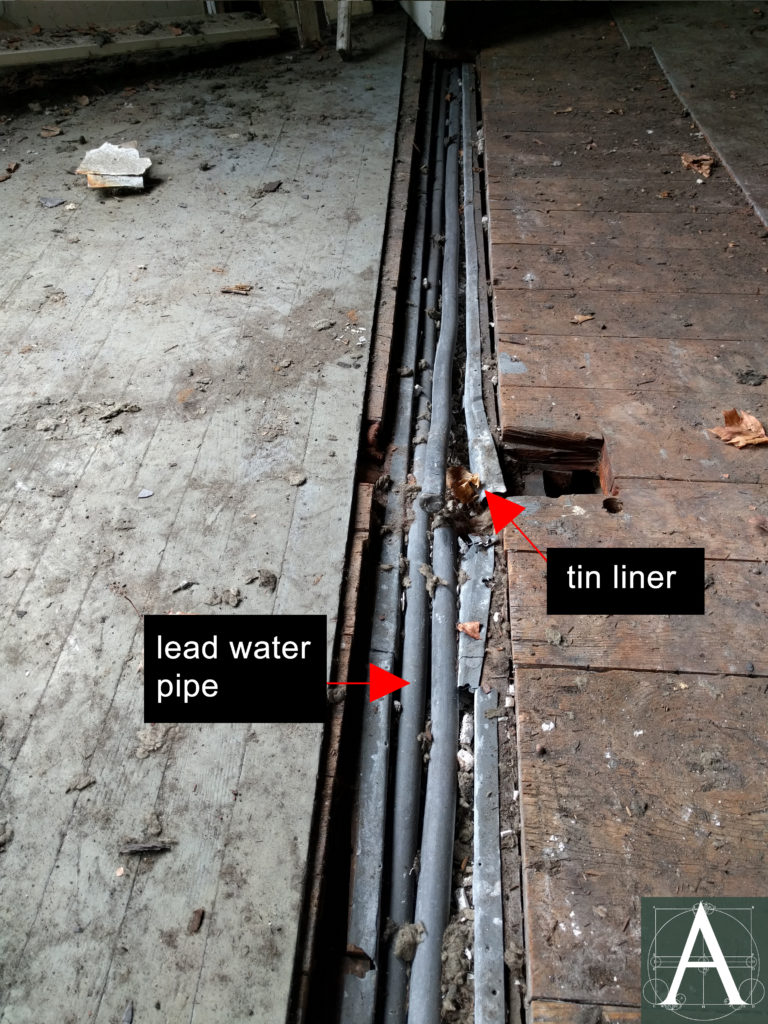

Rare surviving elements of an early plumbing installation remained in the house until 2017. Public water was introduced into Harvard Street in 1861, and it is likely that plumbing was installed in the Conant House shortly thereafter. Plumbing chases containing lead piping were found neatly cut in rectangular channels lined with tin flashing in the floors and walls of the first storey.

Detail of early plumbing installation showing a chase cut in the floor and lined with tin within which lead water lines were laid (ca. 1861) [Courtesy of the Cambridge Historical Commission]

Date

1844, ca. 1861, 1892

Builder/Architect

William H. Hayden & Thomas H. Megroth, housewrights, 1844

William Hovey Junior, architect, 1844

John Quin [sic.], builder, 1892 alterations

Building Type

Side-hall Greek-Revival style house, composed of double parlors on the east side and a stairhall/passageway on the west side of the main house with a rear ell containing the kitchen and service rooms attached to the rear (south) side of the main house.

Foundation

Dressed and rock-faced granite blocks above grade; rubble below grade. At the cellar, bearing points for the house’s frame are supported by monolithic rock-faced granite piers.

Frame

The house is built of braced-frame construction with back-plaster between studs at first and second storeys (attic not available for examination). The frame rests on hewn 8” x 8″ sills with 4” x 12” rough-sawn corner posts and center posts; girts are also composed of 4” x 12” rough-sawn stock. Exterior walls have 2” x 4” studs set at variable distances (13” to 14¼” on center). The spaces between studs are filled with sawn lath (1/4” thick) set vertically and covered with a single rough-coat of lime plaster (variable thickness 1/8” to 3/8”). An air space of 1” exists between the laths and exterior sheathing boards, which are laid horizontally. Diagonal wind braces (4½” x 4”) exist at the tops and bottoms of most junctions of the corner posts and center posts with the sills, girts and plates. All major timbers and braces are joined by mortise-and-tenon joints. Headers for the main staircase and for the two chimneys that existed on the east elevation are framed into the second-storey floor framing with through-tenon joinery. Evidence in the form of open pockets on the north girt at the first storey demonstrates that the bay window is a later addition and replaces two evenly spaced windows that comprised the original configuration of this wall.

Interior partitions have largely been removed, but remaining sections are framed with studs (1 7/8” x 2 ¾”) set at variable distances of 11½” to 12” on center; studs are bridged with toe-nailed braces.

West wall of the main stairhall showing back-plaster set between studs with fragments of finish plaster surviving on fractured lath by the baseboard at the staircase

Detail of the northwest corner showing the corner post and wind-brace of the house’s frame and back-plaster set on vertical lath between studs

Detail of the through tenon at the header for the framed opening for the east parlor chimney (chimney demolished 2017)

East elevation showing Ionic verandah, floor-to-ceiling parlor windows, corner pilasters, main entablature, and parlor chimneys before demolition [Courtesy of Christopher Hail and Cambridge Historical Commission]

Exterior

Although modified by the addition of a two-storey bay window at its façade and the installation of wood shingles on all elevations, the Conant House preserves the majority of its original Greek Revival-style features. The house’s façade is framed by heavy pilasters at each corner that rise to a wide entablature that extends both across the gable and at the rakes to create pediment. The main entry sits within a recessed paneled vestibule approached from dressed granite stairs. The entry is framed at the façade by paneled pilasters that rise to a wide entablature, the crown mouldings of which have been removed. The west (side) elevation was also finished to the same level of refinement as the façade with an Ionic verandah extending the length of the main house. Access to the verandah was through four floor-to-ceiling windows spaced evenly in the house’s double parlors and from a door at the house’s rear ell. Centered on the roof of the main block of the house is an octagonal cupola with wide flat-stock casings forming window frames, panels above and a deep cornice. Its finishes appear original with the exception of 2/2 sash, which may replace original 6/6 sash.

Original exterior finishes are not enumerated in the building contract, except for mention of roof slating at the stable. It is probable that the house was originally clad with a mixture of flush boarding (perhaps at the east elevation beneath the verandah and at the gable) with clapboard elsewhere; however, physical evidence for these claddings has been concealed by added wood shingles.

Cupola showing wide-board trimmings that mimic pilasters, panels and a deep entablature, but without ornamental mouldings [Courtesy of Christopher Hail and Cambridge Historical Commission]

Roof

The main block of the house is enclosed by a pitched roof covered with asphalt shingles. It is probable that it was originally covered with slates, as the building contract cites several points at which progress payments are due to the contractor, one of which is the completion of slating the stable.

Interior

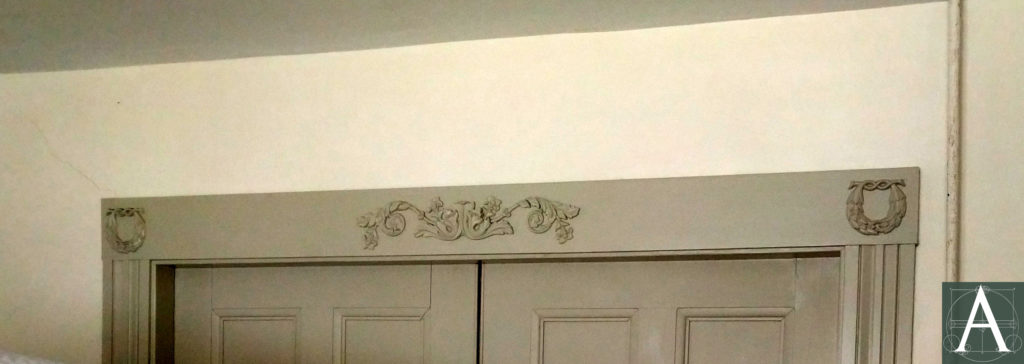

Finishes that survived in the house until 2017 show that the interior was decorated with motifs drawn from architectural pattern books of the day, such as laurel wreaths at window and door heads. The first floor contained double parlors separated by sliding pocket doors on the house’s east side. Walls of the parlors were furred out to provide splayed window embrasures with paneled casement shutters, a detail generally found in ambitious and high-style houses of the period. The building contract confirms that the interior was intended to be finished with wallpaper over the house’s lime plaster walls.

Door case for double doors between east parlors showing pilaster mouldings at the jambs, foliate decoration at the center and laurel wreaths derived from architectural pattern books at the corners (detail demolished 2017) [Courtesy of the Cambridge Historical Commission]

Contributor

Charles Sullivan, City Planner & Historian

Brian Pfeiffer, Architectural Historian

Sources

City of Cambridge, Massachusetts. Cambridge Historical Commission. Research file for 330 Harvard Street.

Middlesex County Registry of Deeds.

- Book 346 pages 414-415 – Deed Restrictions recorded November 2, 1835

- Book 445, pages 488-489 – Building Contract dated July 1, 1844.

Hail, Christopher. Harvard/Radcliffe Online Historical Reference Shelf Cambridge Buildings and Architects. http://hul.harvard.edu/lib/archives/refshelf/cba/

Ryder, Calvin. Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Maine. Maine Office of Historic Preservation, Augusta, Maine. http://www.state.me.us/mhpc/architects_bio.html