Notable Elements

- eelgrass insulation [Interior]

- circular cellar and evidence of 1834 rainwater drainage system [Foundation]

- reused timbers and chimney (partial) from earlier structure [Frame]

- lime plaster repaired in-kind, 2015 [Interior]

- undisturbed Greek Revival-style woodwork and 19th-century hardware [Interior]

History

The Nicholson-Andrews House is a notable example of transitional Federal/Greek Revival architecture in Nantucket that preserves all the major elements of a vernacular house type, known locally as a “Typical Nantucket House.” The house’s exterior design with its asymmetrical façade, paneled front door set within a pilastered surround, window cases with splayed wooden lintels, and undecorated plank frame window cases at rear elevations are characteristic of the good building practice during Nantucket’s whaling era that made the community wealthy from the eighteenth century until the collapse of whaling in 1848.

Unoccupied and unmodified for nearly sixty years from 1956 until its conservation and restoration in 2015, the building preserves the vast majority of its interior character-defining features without the intrusion of modern plumbing and heating systems. Among the significant architectural elements that remain are the house’s floor plan, lime plaster walls and ceilings, softwood floors, paneled doors, moulded & paneled interior window trimmings, moulded baseboards, mantelpieces and balustrades. The central chimney remained in position, capped only to a point beneath the roof deck in the mid-twentieth century, together with its six original fireplaces, the openings of which were blocked with masonry that protected the fireplaces from alteration.

Façade & south elevation (2005) showing adding shingle siding; chimney capped below the roof ridge following lightning strike ca. 1960

The house stands in a portion of Nantucket that was laid out in 1726 as the West Monomoy Lots. Development in the area occurred slowly. Land on which the Nicholson-Andrews House stands was part of a larger parcel purchased in 1834 by John B. Nicholson, house carpenter, (1791-1859) from Peleg Macy, Junior. Known to have been an active builder/speculator, Nicholson subdivided the parcel and subsequently sold it as five lots with houses standing on each. A number of buildings constructed by Nicholson have been identified throughout Nantucket, including a nearby Federal/Greek Revival-style house at 44 Union Street that shares many details of moulding profiles, mantelpieces and woodwork with the Nicholson-Andrews House.

On December 19, 1835, Charles G. Andrews, master mariner, purchased the property from Nicholson for a price of $1,600 under a contract that stipulated: “windows of the house next south are not to [be] darkened by [placing] anything in the adjoining passageway,” indicating the presence of adjacent houses presumably built by Nicholson. Following Andrews’ death in 1839, his widow, Eunice, sold the house in 1842 to David Smith, who, in turn, sold it to George Myrick, merchant, in 1848. In 1855, Myrick sold the house to Joseph Simmons, mariner, who acquired the adjacent lot to the south and brought the property to its present size in 1864. In the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, the property was reacquired by the Andrews family who retained ownership until 2014. In the second decade of the twentieth century, the house was adapted to multifamily occupancy, as well as use as a lodging house during the Great Depression. The last occupants of the house moved out of it in 1956 after which it remained vacant and used for storage, until 2014-15 when conservation repairs were made to restore the building to single-family use.

Date

1834; salvaged elements from ca. 1760-80; repaired and restored 2015

Builder/Architect

John Nicholson, house carpenter, 1834

Conservation repairs carried out 2015: Penelope Austin, lime plasterer and mason; Michael Burrey, preservation carpenter

Building Type

Typical Nantucket House: Characteristic of its type, the building’s timber frame is composed of four structural bays arranged as two-bays in width and two bays in depth without a chimney bay. Lacking a separate chimney as would be customarily found on the mainland, the building’s central chimney occupies the northeast corner of the southwest bay where it rises through the structure as two pieces set at right angles to each other. The southern portion of the chimney contains back-to-back fireplaces (east and west) serving the southeast and southwest rooms, while the northern portion contains fireboxes serving the northwest rooms. The flues come together at the head of the second storey to form a single mass at the attic. The placement of the chimney allows the creation of four rooms per storey including an unusually large, square two-storey stairhall at the building’s northeast corner. Rooms at the building’s southeast, northeast and northwest corners occupy the full size of the timber-frame bays in which they sit, while rooms at the southwest corner are reduced in size because of the space occupied by the chimney mass.

Characteristic of Typical Nantucket Houses constructed in the first half of the nineteenth century, the Nicholson-Andrews House has an original kitchen ell at its northwest corner. More lightly framed than the main body of the house and with lower floor heights, the kitchen ell appears never to have had a kitchen hearth, but rather a cooking range, as the ell’s chimney contained a single flue with no evidence of alteration or removal of a fireplace or bake oven.

Floor plans of the 1st & 2nd storeys showing characteristic layout of rooms in a “Typical Nantucket House”

Foundation

All sills at the main block of the house and its ell are supported on rubble-stone footings with the exception of the northeast corner of the main house where a brick foundation wall surrounds the northeast corner of the structure, within which is an original circular cellar constructed of brick with brick flooring. Circular cellars are a distinctive element of vernacular building on Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard and Cape Cod. They are believed to be an adaptation to sandy soils and the pressure they exert on walls; the circular form employs the strength of an arch and is strengthened by the soil pressure, unlike a straight wall, which would tend to bow and collapse under the pressure of loose, sandy soil.

Partial view into the north side of the circular cellar showing the curved brick wall and brick-paved floor

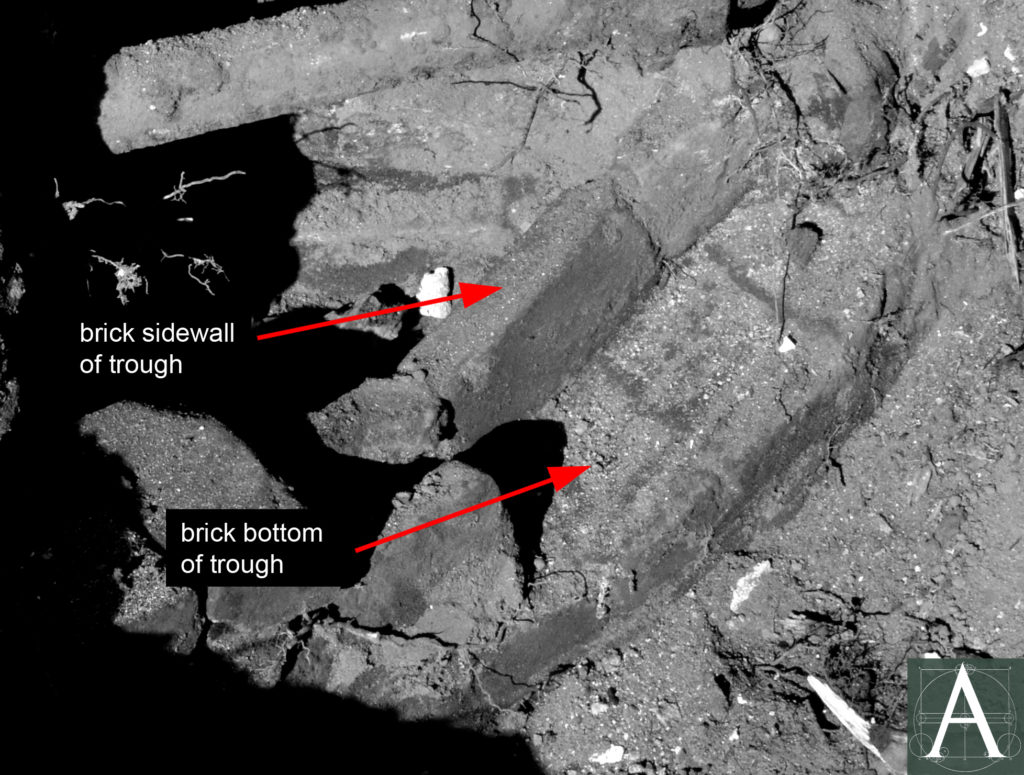

During 2015 repairs to the building, evidence of an original rainwater drainage system was found at the southwest junction of the main house and kitchen ell. The system consisted of a brick-lined channel that led from a corner downspout to a domed brick cistern set below grade level.

Brick-lined rainwater drainage channel leading from southwest junction of the main block and rear ell to a brick cistern, possibly original to 1834

Frame

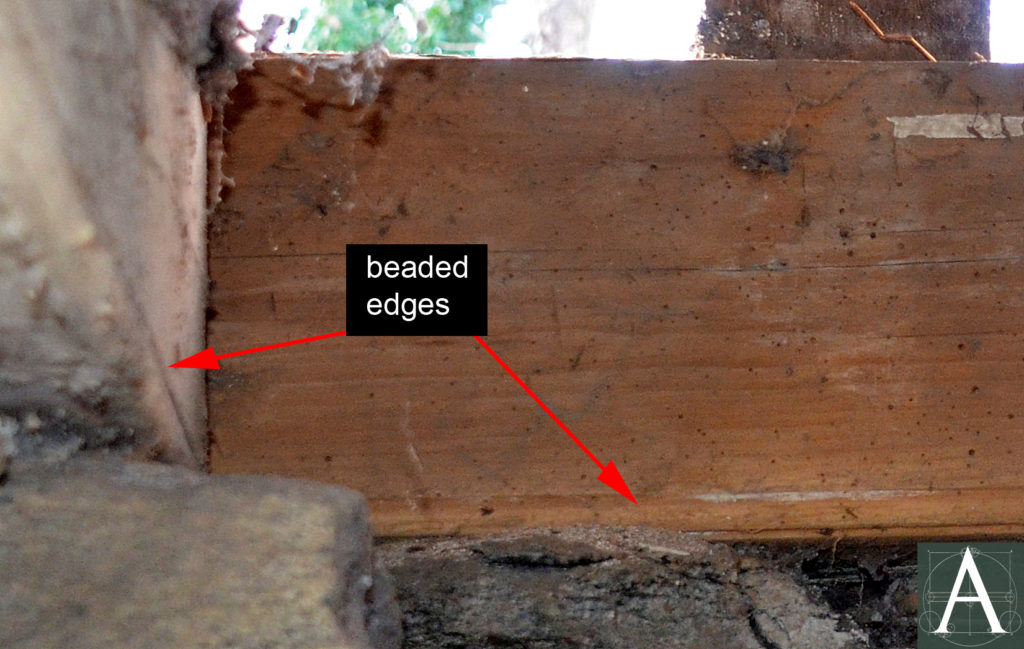

Characteristic of its building type, the house’s timber frame is composed of four structural bays and lacks a chimney bay. Structural timbers visible at the crawl space appear to have beaded edges with empty pockets for joists, indicating that they were salvaged from a house of the late eighteenth century. Other timbers at the upper floors appear to be a mixture of salvaged timbers and newly-milled timbers from 1834. Local deeds suggest that a pre-existing house stood on the parcel acquired by John Nicholson in 1834. It is possible that salvaged timbers in the building came from this source. Additional support to this theory exists in a section of earlier brickwork within the chimney and at the chimney’s base, which consists of rubble laid on grade without sleepers or an arched base and sections of clay mortar.. Decorative painting found on the underside of a floorboard that was exposed during plaster repair provides additional evidence of the role of salvaged materials in the house’s construction.

West sill at main block of house showing hewn surfaces and empty pockets from its original use in a late-18th century house

West sill at main block of house showing beaded edge from its previous use as an exposed interior timber in a late-18th century house

Decorative painting on the underside of a sheathing board, reused for sub-flooring in 1834 and concealed by original plaster

Exterior

The exterior presents an appearance characteristic of its type and period in Nantucket. Originally covered with clapboards on its façade and north elevation, and shingles on its less visible elevations, the house displays a hierarchy of formal and less formal finishes. The façade, the north elevation of the main block of the house and the eastern windows of the south elevation that illuminate the front parlor and parlor chamber were fitted with windows set in cases with half-round mouldings and applied trapezoidal lintels in imitation of a popular masonry detail of the Federal period. As these elevations were prominently visible from the street, such elements were intended to present a stylish appearance. Window details at the kitchen ell, the western half of the south elevation and the rear (west) elevation of the main block of the house were set in standard (and somewhat old-fashioned) plank-frames with sash containing smaller lights than the larger-paned 6/6 sash that provided light to the house’s front rooms.

Architectural finishes at the façade include a pilastered entry capped by an entablature with a band of stylized modillions beneath its crown moulding, a detail that is matched at the main cornice of the façade. An early or original open deck extended across the façade and was reconstructed in 2015 to match the appearance shown in historic photographs. Bearing details seen in other houses of the period, the deck was surrounded by a balustrade composed of square balusters and tapered newels beneath a rounded handrail.

Additional exterior elements include:

- Masonry – [Foundation]

- Roof – The main block of the house is enclosed by a simple pitched roof without dormers. Near the ridge at the rear (west) slope is an original hatch and ladder that provided access for cleaning the chimney flues.

Interior

The interior of the main block of the house survives with no modern alteration to its original plan and with nearly all its original finishes intact. Among the interiors many notable elements are:

- Plaster: Walls throughout the house are uniformly lime and hair plaster applied to sawn wooden lath. During conservation repairs, damaged areas of plaster were cut back to sound plaster, their edges beveled back to provide a key and lath was repaired. Beveled edges and exposed lath were dampened down with lime water to reduce suction after which lime-and-hair plaster was installed to fill cracks and missing sections. Repair plaster was made of a 1:3 ratio lime:sand mix, using high-calcium lime putty that had been slaked six months prior to use and three parts sharp, well-graded washed sand. Goat hair was added to reduce shrinkage and cracking; its proportions varied by location (wall or ceiling) and depending upon whether the original installation was a one- or two-coat application of plaster.

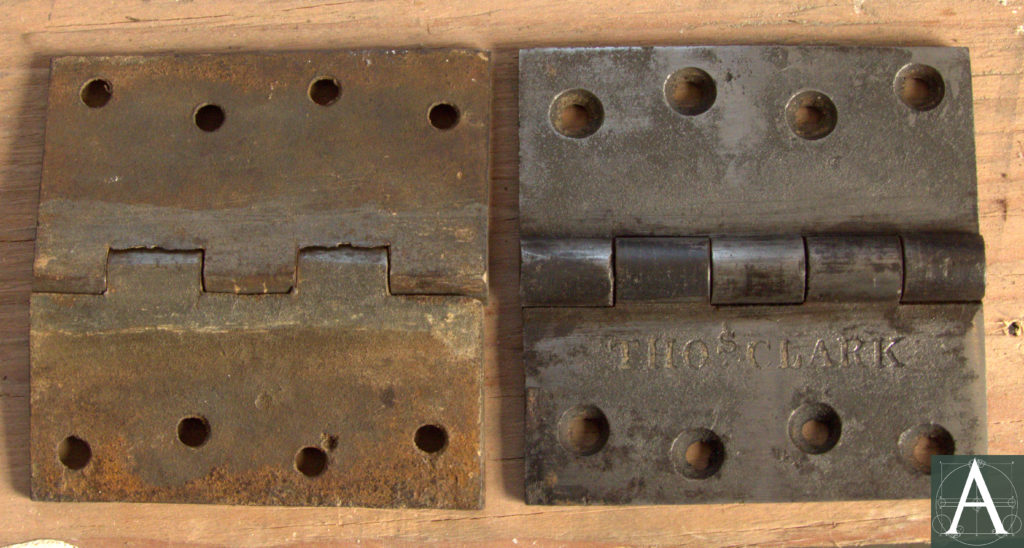

- Interior woodwork in the main block of the house is intact from 1834. It consists of six-panel Greek Revival-style doors, mantelpieces with moulded pilasters or engaged columns and deep entablatures, and baseboards. Window and door surrounds are framed with moulded architraves except at the first-storey parlor where they are framed by pilaster mouldings with corner blocks. First-storey windows were fitted with paneled casement shutters set on iron shutter hinges either at the time of the house’s construction or early in its history. All of interior shutters were removed and stored in the attic by the early twentieth century; these shutters and their hardware have been reinstalled in positions indicated by the scars from original hinge attachment points.

Detail of Greek Revival-style mantelpiece at the first-storey northwest room of the main block of the house

Detail of Greek Revival-style mantelpiece at the first-storey southeast room (parlor) of the main block of the house

Detail of interior shutters that were installed on all windows at the first storey of the house’s main block (ca. 1850-60)

- Central chimney: The chimney rests directly on a base of fieldstone and brick set directly on grade. The core of the chimney retains fragments of earlier masonry laid in clay mortar; however, evidence of earlier fireplaces does not survive. All six existing fireplaces date from 1834 and survive in their original form. There is also no evidence of a cooking hearth at the central chimney, which indicates that the rear ell was integral to the 1834 design of the main block of the house. All mantelpieces are original and contain fine Greek Revival-style mouldings, pilasters and columns.

- Window sash: Sash dates mostly from 1834 and consists of 6/6 double-hung wood windows; fragments of 12/12 sash survived on the rear wall of the main block of the house and at the rear ell set in plank-frame surrounds. It is likely that these windows with their smaller panes and simpler trimming were a concession to economy on the rear elevations.

- Eelgrass insulation was found in the west wall of the main block of the house. This once abundant material was used for insulation in numerous coastal locations around New England, but went out of use after 1930-31 when a wasting disease killed nearly 90% of the eelgrass beds of the North Atlantic.

- Hardware: Nearly all the doors and casement shutters preserve original hardware: cast-iron front door hinges bear the stamped maker’s mark “Thos. Clark”; cast-iron shutter hinges are not marked.

Original cast-iron hinges from front door bearing maker’s mark of “Thos. Clark”; repaired and reinstalled, 2015

Contributors:

Penelope Austin, lime-plasterer and mason; Michael Burrey, preservation carpenter; Brian Pfeiffer, architectural historian

Sources

“The Andrews Home, 55 Union Street, Nantucket, MA,” Preservation Institute, Nantucket, 2005 – Nantucket Historical Association

1890s Photograph of 55 Union Street, Nantucket Historical Association: – Nantucket Historical Association