![Central Square Congregational Church, ca. 1880, 71 Central Square, Bridgewater, MA showing the original spire [image from Digital Commonwealth: Clement Maxwell Library collections at Bridgewater State University]](http://www.archipedianewengland.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/PHOTO-01-Central-Square-Church-ca.-1880-frm-Brdgwtr-State-U-Commons-VMC022-637x1024.jpg)

Central Square Congregational Church, 71 Central Square, Bridgewater, MA – view ca. 1880 showing the original spire [image from Digital Commonwealth: Clement Maxwell Library collections at Bridgewater State University]

- Original foundation ventilation [Foundation]

- Unique unweathered M.F. tin roof and pre-1900 asphalt prepared roofing [Roof]

- Original wooden ventilation system [Interior]

- Regionally characteristic pattern of church construction by subscription & pew rentals [History]

- Italianate architectural details [Exterior & Interior]

- Partial maintenance history [History]

History

First organized as the Trinitarian Congregational Church of Bridgewater on October 21, 1821 in the Scotland section of Bridgewater, the congregation moved in 1836 to the center of Bridgewater where it used the Bridgewater Academy (demolished) for several months until a meetinghouse could be constructed on the site of the current church. Dedicated as the First Trinitarian Congregational Church of Bridgewater, the building was destroyed by fire on August 6, 1860 and replaced by the present structure in 1861-62.

Building the Church and managing the pews: Following a pattern characteristic for the construction of Protestant churches in New England, the congregation formed a corporation of Proprietors to raise money for the construction of a new church by paying subscription shares. Once built, the new building was rented to the religious society on five-year leases, an arrangement continued from December 26, 1863, when the Central Square Society of Bridgewater was incorporated as the owner of the building and the First Trinitarian Society of Bridgewater became its lessee, until 1904 when the two entities merged.

Church records refer to the entity that owned the church as “the Corporate Church” and to the religious society as “the Society.” Financial support of the society was a contentious issue in the 1860s and 1870s. Unlike many Protestant religious societies that granted deeds for pews to individuals who subscribed to build the meetinghouse, the First Trinitarian Society conducted an annual auction at which parishioners bid for the choice of pews to rent. During the early years of the new church, rents were routinely inadequate to support the ministry and care of the building. By January 1873, the church’s finances were troubled by chronic “arrearages” and resistance arose to the annual auction to sell the choice of pews for rent, even though such auctions raised as much as $1,404 in 1868 alone. In its report, the committee that was appointed to solve this problem stated:

…..It may not be known to all of the congregation that the funds for building and furnishing this church were given to the Corporate Church and society connected therewith on the condition that when the church is completed the pews shall be let at an annual rent to be paid quarterly which shall be applied to the support of preaching the Gospel in said church and to defray the ordinary expenses connected therewith…..the question which has been often asked, why is the matter of renting the pews brought up every year?

The committee further reported that in the years 1862-1868 annual budget deficits frequently rose as high as $400, and that for the “the last five years the sum received from pew rents and the premiums at the sale of the choice of pews” continued to be insufficient to pay the congregation’s costs creating “arrearages.” These shortfalls were made up by separate appeals (subscriptions) to parishioners. The committee noted that those who paid the highest pew rents were also the largest subscribers to make up the deficits. It further observed:

Subscription papers for arrearages and various other purposes have of late come so frequently that they have lost the charm of novelty, and fail to excite any pleasant emotion. A large number of the Church and Society regard them with a decided feeling of aversion because of the great perplexity one experiences in deciding how much to subscribe on any one of these papers…on account of not knowing how many more subscriptions papers will come…

The congregation accepted the committee’s proposal to allow pewholders to retain their pews from year to year rather than bidding annually, but it rejected the proposal for “the sale of choice pews” as a way of raising money. The question of pew rentals and subscriptions remained in active debate at least until 1904 when the Religious Society and the Corporate Church finally merged into a single entity.

Architectural History: Plans for the new church were drawn up immediately following the fire that destroyed the previous meetinghouse. Although an initial vote authorized a brick structure in the Gothic style, the cost of this plan may have exceeded the congregation’s financial capacity. The present wood-frame, Italianate-style church was built at a total cost of $7,224.80 and dedicated on May 18, 1862. The building retains a high proportion of its original finishes in the form of heavy rustication at the corners of the bell tower, window heads with label mouldings, flush boarding, ornate brackets at the open eaves, and extensive interior finishes.

The building’s architect, Solomon Keith Eaton (1806-1872) was a native of Mattapoisett, Massachusetts, who maintained an active architectural practice in New Bedford, Massachusetts. His architectural designs ranged across the various early and mid-Victorian styles that became popular during his lifetime. In Bridgewater, he designed the Bridgewater Town House (Central Square, 1843) the First Parish Church (50 School Street, 1845), and what is now the rear wing of the Bridgewater Academy (Central Square, 1868).

Maintenance History: Church records provide insight into the challenges of maintaining a large church building during the nineteenth century and the changes that technology made in the utility systems considered necessary for the building. Exterior painting stands at the top of the maintenance list as one of the most frequent and expensive obligations, but redecoration and reconfiguration of parts of the auditorium were also frequently considered. Among the maintenance work noted in church records are:

- Exterior: Votes for exterior repairs, frequently painting, typically resulted in the formation of a committee to obtain estimates. The time between gathering estimates and authorizing the work depended upon the congregation’s ability to raise money. Often a lapse of two or three years occurred. Exterior repairs were needed in the following years:

- 1867 – vote taken to repaint and to assess pew holders 25% of their annual rent to cover the cost

- 1877 – vote taken to paint the exterior as soon as the money was raised to cover painting and arrearages

- 1890 – accepted painting proposal of $275; raised $242 by 1891

- 1913 – voted to seek proposals for painting; 1914 committee reported it could find no painters to bid; unclear if and when painting took place

- 1917 – voted to consider changing the design of the front door

- 1927 – consider shingling the church (perhaps to reduce the expense of painting clapboards and flush-boarding) and investigated types of shingles possible for this purpose

- 1952 – exterior painted; steeple & roof repaired

- 1960 – spire removed and replaced with shorter spire

- Interior

- 1883 – “voted to paint and fresco the interior of the church” and a new organ loft built at a cost of $1,700

- 1900 – estimates sought for “painting, decorating, and carpeting the church”

- 1912-13 – voted to remove the front pew carefully and store it in the attic

- 1915 – removal of rear row of pews authorized at discretion of the Welcoming Committee

- 1926 – committee authorized to study question of redecorating the church auditorium

- 1927 – interior renovation authorized with members of committee charged with raising the money to cover it over a period of three years; renovation of auditorium by L. Richmond & Co. from Boston for a cost of $3,473

- 1935-36 – “consider plans for the rearrangement of the front part of the Auditorium” after the removal of the old organ

- 1940 – voted to get plans & estimates for redecorating the interior of the auditorium

- 1956 – report delivered on “the progress of work in the Auditorium”

- Lighting:

- 1874 – voted to purchase additional lights and shades for the Vestry

- 1891 – considered electric lighting but deferred the question until money raised to pay for painting – lighting installed in Vestry by 1892

- 1902 – committee authorized to consider better lighting for the Vestry

- 1913 – voted to change electrical wiring as needed

- 1916 – clock tower illuminated

- Heating:

- 1887 – vote “to consider what actions to take with regard to better heating and ventilating of the church”

- 1893 – committee authorized to “purchase and set such furnaces as in their judgment seem best” – work apparently not implemented

- 1894 – second consideration of heating the church

- 1913 – voted to bring gas into the building before the ground freezes

- 1926 – consider plan to reorganize the heating system

- 1936 – voted to install new furnace

- 1947 – no action taken on new furnace because of prohibitive prices

- 1952 – cost of heating installation reduced to $900 – [not clear if installed]

- Miscellaneous Repairs:

- 1873 – volunteers graded the ground around the church and put up a fence

- 1897 – new “hard-pine floor” installed in the Vestry

Date

1862

Builder/Architect

Solomon Keith Eaton (1806-1872), architect

Ambrose Keith, master builder

Building Type

Church

Foundation

Rock-faced granite blocks stand on a footing of rubble masonry that extends around the perimeter of the original church building enclosing a crawl space with a dirt floor. At three locations on the east and west elevations of the main body of the church hall, granite blocks have gaps of approximately 3” between them to allow air to circulate within the crawl space as a means of reducing the effects of rising damp from the soil. These gaps are currently filled with hardware cloth to prevent vermin from entering; the original material used for this purpose is unknown. It is unusual to find foundation ventilation during this period, as most foundations contained a high proportion of rubble stonework which created vapor permeability through its lime mortar joints and gaps in the laying of the irregularly shaped stones. The ventilation system found at the Central Square Church was probably designed in recognition that the dirt floor of the building’s crawl space would have caused moisture to evaporate and be trapped by the large vapor-impermeable granite blocks that surround the crawl space; allowing air exchange with the outside would have reduced moisture and condensation. This system was augmented prior to 1916 by the installation of two rectangular vents, one on the east elevation and one the west. These vents were cut between studs and covered with wire cloth to allow air to circulate freely from the exterior through the crawl space. The vent on the west elevation was closed in the mid-twentieth century, while the vent on the east remains open.

Added vent between studs at the east elevation to provide air circulation to framing and crawl space

Frame

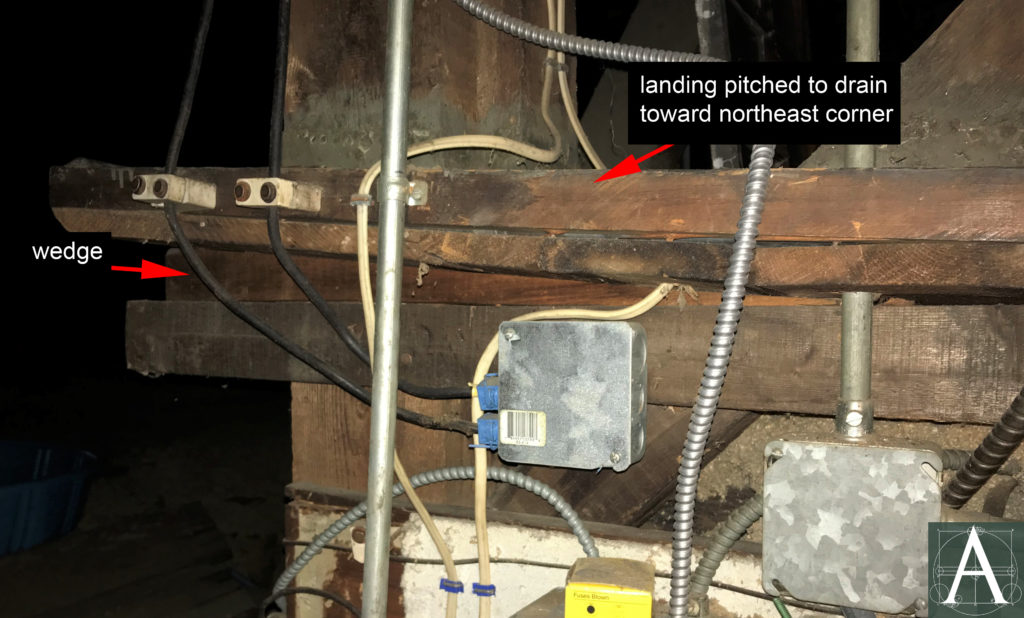

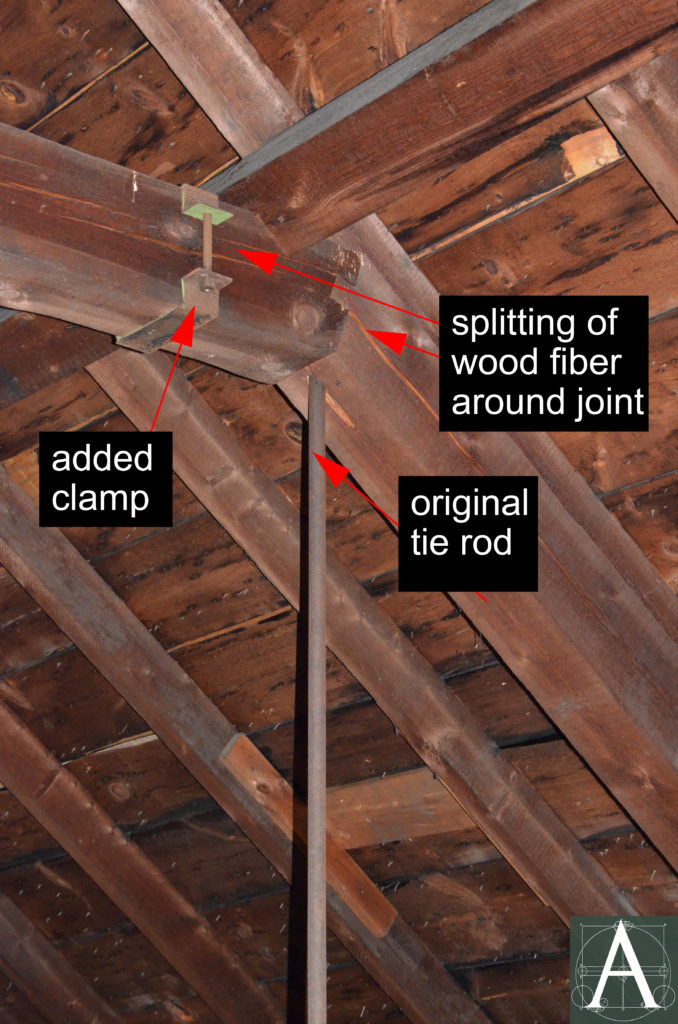

Braced frame construction: The building is constructed in a traditional manner with large dimension (8” x 8”) sawn timbers fitted together with mortise-and-tenon joinery. The frame is composed of six bents forming five bays at the auditorium. At the attic, bents have modified queen-post trusses with iron tie rods in the position of queen posts. Trusses appear to have undergone a uniform repair at the junction of each top chord with a side strut; checks in the timbers suggest some stress in the structure that was resolved by installing iron clamps around the ends of each top chord.

Deep checks in the wood grain of the top chord of the roof trusses – repaired with added iron clamps

Exterior

As originally constructed, the church’s exterior was clad with flush-boarding at the façade (south elevation) and at the first storey of the east and west elevations. The upper floor and rear elevation were covered with clapboard. Notable elements include the rusticated quoins at the corners of the façade’s first storey, the deep brackets at the building’s open eaves, and the arched and flat-head window openings with label mouldings. While window sills are 4” thick, a dimension that is typical for buildings of this scale and period, they are made of two pieces laminated together rather than a single piece. Windows of the upper floor (auditorium) are composed of double-width sash rising to arched heads. Sash throughout the building has been replaced, probably in the early twentieth century; while it matches the configuration of original sash, its moulding profiles do not. Original sash remains only in windows at the first storey of the projecting portion of the façade.

The original front door was composed of three leaves set in a paneled surround that filled the entire archway. This arrangement was modified around 1917 by the installation of a Colonial Revival-Style doorway composed of two raised-panel doors surmounted by a glazed fanlight.

Roof

The original roof covering of the church’s auditorium remains unknown. One reference in the church records mentions replacing “broken tiles on the roof;” however, it seems unlikely that the roof was ever covered with ceramic tiles or asbestos shingles, which are sometimes called tiles, nor is there evidence of slate. It seems probable that the main roof was covered with wooden shingles, but there is no documentation of it. The church’s tower preserves three original or early sections of roof, all presumably installed to offer extra protection from potential leaks in the tower.

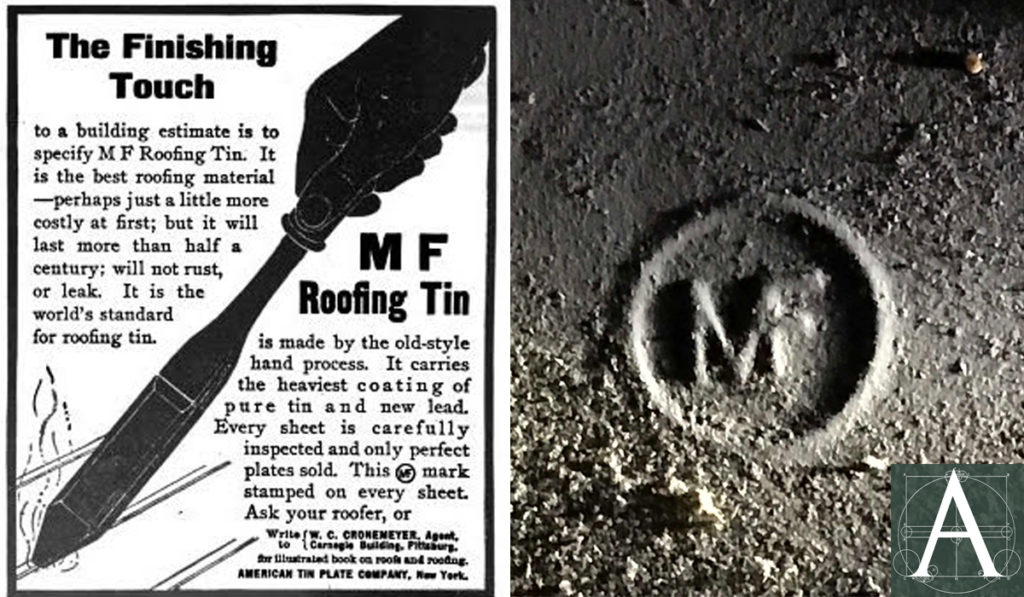

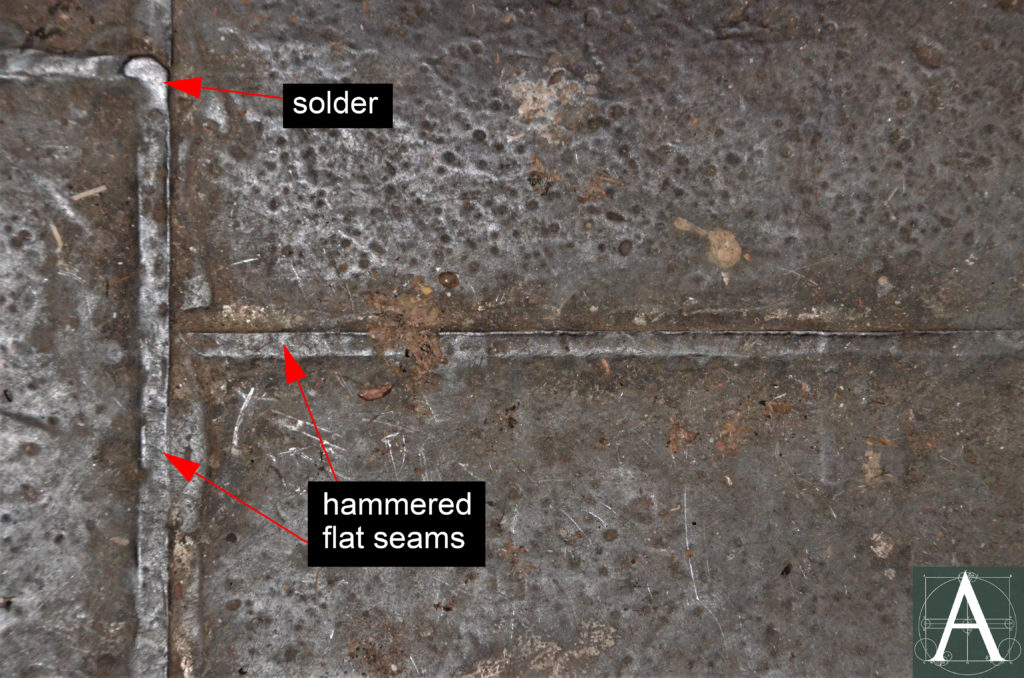

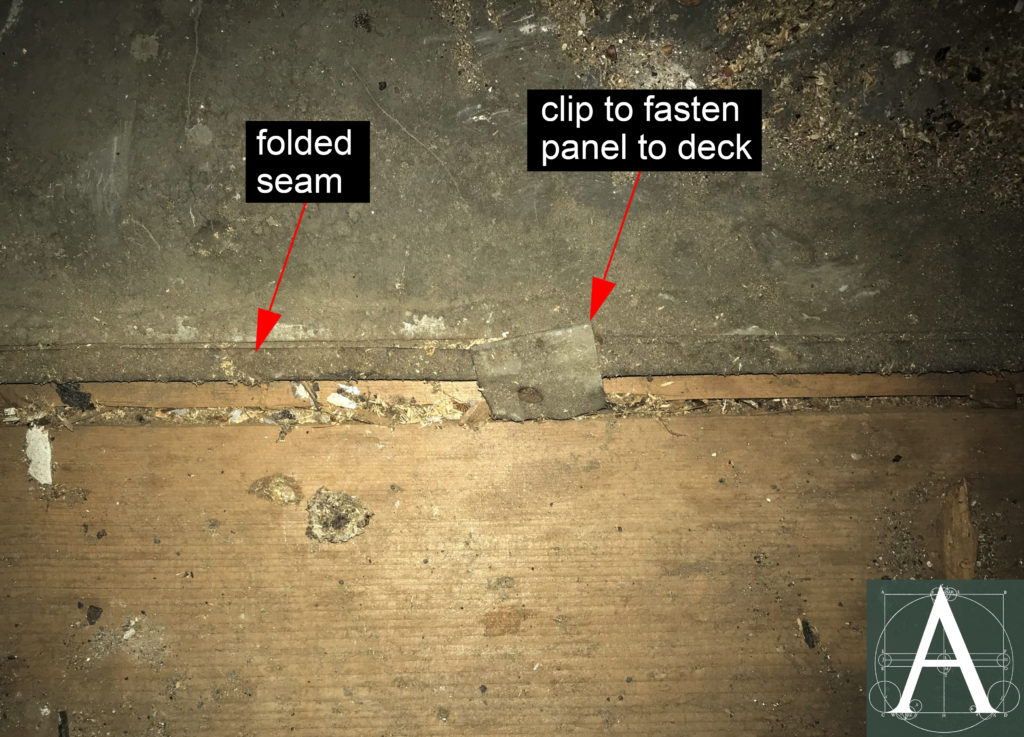

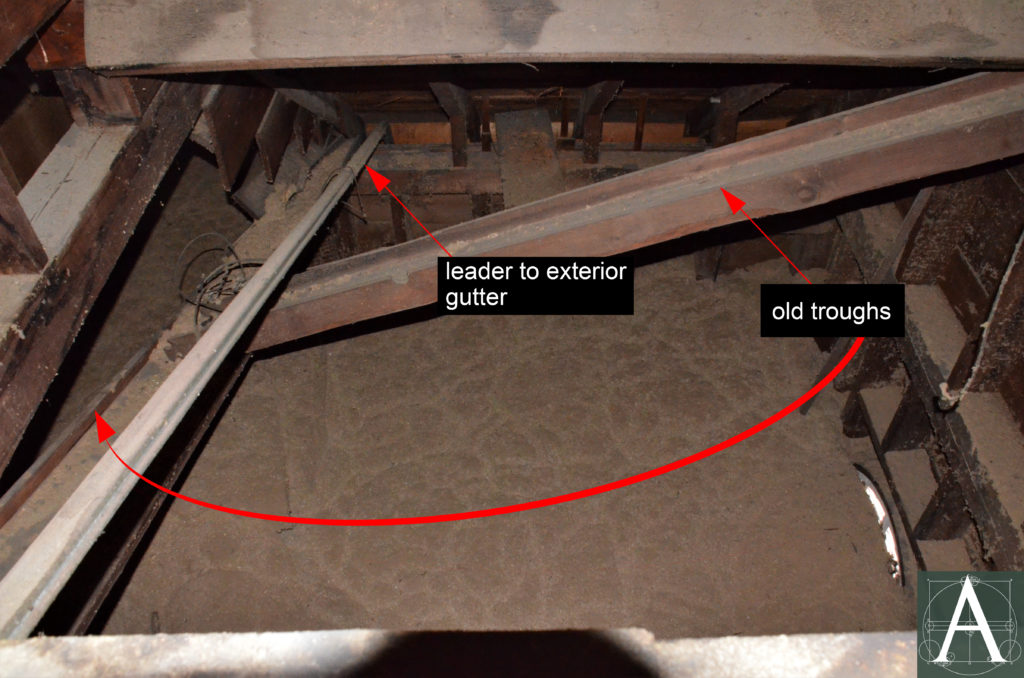

Tin-plate roof: The building preserves an exceptionally good example of mid-Victorian tin-plate roofing at the interior of its tower. Located between the organ loft which occupies the second storey of the tower and the first landing of the tower above the main roof is a half-height space, the floor of which is roofed with a tin-plate roof, presumably as a second level of protection of the interior against leaks in the tower. This roof is set on decking that has been raised by wedges on its west and south sides to provide a continuous pitch to its northeast corner where a downspout runs diagonally down through the attic to join the east gutter of the façade’s projecting pavilion. The edge of the roof is framed by a raised curbing that has been covered with tin-plate roofing as have all the studs and framing members that rise to the next level of the tower. The roof is made of rectangular sheets of tin-plate 19” x 27” fastened to the roof deck with clips and seams that have been folded, hammered and soldered. Many of the plates bear an embossed trademark “MF” which was mistakenly believed by many workmen to stand for “Most Favored.” The “MF” brand came from the original maker of this material, the Margram Forge in Port Talbot, Glamorganshire, England. The Margram Forge sold rights to make this material to the American Tin Plate Company which modified the galvanizing process slightly to improve the uniformity of the thickness of the tin-plating on the sheet iron’s surface. During the second half of the nineteenth century, this material was widely used as a first-grade roofing for bay windows, verandahs, towers, and other low pitched roofs, the majority of which have since corroded and been replaced. Protected from weathering, this roof provides a unique example of the material and nineteenth-century installation practices.

Tin-plated roof panel showing a clip to fasten it to the roof deck and the open half of an interlocking seam between panels

Metal leader from internal roof to east eaves; also an earlier system of wooden troughs, perhaps to drain leaks from the tower

1862 (?) Wood Shingle Roof: The floor of the belfry is a low-pitched hip roof covered with wooden shingles that may be original to 1862. The shingles have moderately weathered surfaces, but would never have been exposed to full weathering and sun. The installation seems to have been partially renewed with asphalt shingles laid over its ridges at the time that the spire was replaced (1960).

Low hipped roof at the bell-landing with original wooden shingles (1862) and added asphalt shingles at the ridges (1960) – lower left of photograph

Pre-1900 composite rolled roofing (?): The upper landing of the tower directly beneath the belfry contains a large box or cupboard constructed of beaded tongue-and-groove boarding. The purpose of this structure is not documented; however, its top is covered with a layer of composite roofing, perhaps an asphalt-impregnated cloth or other early form of asphalt prepared roofing. The surface has an alligatored-texture and lacks the mineral granules that were added to asphalt roofing after 1897 to increase the material’s durability. The sheets are tacked in place with galvanized roofers’ nails that appear to have been coated with tar or asphalt.

The formal spaces of the church’s interior consist of an entry hall with curved staircases leading up one storey to the auditorium and organ loft. Characteristic of its period, the interior is finished with a variety of heavily moulded door and window cases, paneled doors, high baseboards, curved railings, and iron hardware. An unusual survival can be seen in the louvered interior shutters which retain their original brass spring latches.

Ventilation

Victorian public buildings frequently included carefully considered provisions for ventilation due to the era’s concerns about the transmission of tuberculosis, which was then incurable. The Central Square Church seems to have been fitted with such a system from it initial construction. As early as January 1871, the congregation established a committee “to consider the ventilation of the church.” The committee recommended that the “ventiducts in the Church be continued to the belfry” and that “four portable window ventilators” be purchased. While the portable window ventilators no longer remain, much of the “ventiduct” system survives in the attic and in the belfry where it rises to a now-blocked opening in the belfry floor, as proposed in 1871. The system consisted of grilles (now removed) set high on the walls of the auditorium that were connected by wooden ducts to the belfry where an open vent created a draw allowing warmer air to rise and pull cooler fresh air from lower down in the church. It is not known when this system was abandoned and its grilles removed.

Contributor

Brian Pfeiffer, architectural historian

Sources

Central Square Congregational Church. “Central Square Congregational Church, United Church of Christ, Bridgewater, Massachusetts, 1821-1983.” [manuscript].

Clerk’s Records of the Central Square Congregational Church, Vol. 1, 1863-1904; Vol. 2, Committee Reports Ledger, June 1904 – May 1959.

Massachusetts Historical Commission. Bridgewater Historical Inventory, Form BRD.51 http://mhc-macris.net/Details.aspx?MhcId=BRD.51.

New Bedford Historical Society: “Three Victorian Architects of New Bedford.” [Solomon Eaton] http://www.oocities.org/nbps2000/ThreeVictorianArchitects.pdf.

Wikipedia: Asphalt Shingle. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asphalt_shingle.