Notable Elements

- Central chimney laid up in clay mortar and faced with lime mortar [Interior]

- Possibly pre-fabricated timber frame [Frame]

- Circular cellar [Foundation]

- Interior finishes include extensive vertical sheathing with shadow mouldings & lime plaster [Interior]

History

The Silas Paddack House is a one and one-half storey timber frame cottage built ca. 1767 for Silas Paddack, mariner, on land inherited from his wife’s family. Mariner Silas Paddack, who was the first owner of this house, was the great-nephew of Ichabod Paddack, a Cape Codder who had been invited to Nantucket in 1690 to teach the craft of whaling. By the mid-eighteenth century Nantucket was one of the world’s leading centers of whaling and the production of whale oil, and Silas Paddack was a participant. After the Revolutionary War, Paddack and his family moved to Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, with about a dozen other Nantucket families to set up a whaling center there, but it was not successful. Captain Silas Paddack died at sea on his way to Halifax in 1795, and his family returned to Nantucket, but not to 18 India Street, as they had sold the house in 1791. The next owner of 18 India Street, mariner William Barnard, served as first mate on the ship Leo in 1797 when the captain was killed by a whale, gaining Barnard promotion to captain. Following the death of William Barnard in 1804, his daughter, Nancy Starbuck and her husband, Josiah, occupied the house. They sold it in 1816 to her brother, Frederic. The house was purchased by Peter G. and Lurana Chase in 1821. The Chase family occupied the dwelling until 1829 when it was sold to George Paddack. His descendants sold to George H. Mackay in 1920. In 1942, the property was purchased by George B. and Grace Yerkes.

Local tradition reports that the small one-story shed was added to the building’s west side was a “rum shop”; however, physical evidence demonstrates that the structure was built as part of the house’s original construction. Whether rum was sold or another business conducted there, it was not uncommon for Nantucket women to supplement their seafaring husbands’ unpredictable incomes with enterprises of their own.

Dates

1767

Builder/Architect

Original builder unknown; conservation repairs carried out 2006-2007 by: Penelope Austin (lime plasterer/mason), Michael Burrey (preservation carpenter), Robert Mussey Associates (conservation of decorative finishes), Newton Millham (blacksmith for repair & fabrication of restoration hardware) and Brian Pfeiffer, architectural historian/project manager

Building Type

Typical Nantucket House: Characteristic of a large number of houses built on Nantucket before 1850, the cottage is framed as two bays in width and two bays in depth, but lacks the separate chimney bay found commonly in contemporaneous timber-frame buildings throughout New England. [see Frame]

Foundation

The house stands two feet above a crawl space that is enclosed by a foundation wall of dry-laid rubble stone, some of which is not native to Nantucket and is traditionally believed to have come from ballast. A shallow brick cellar with a brick floor exists beneath the house’s northeast corner; its curved walls derive from the practice of building circular cellars in Nantucket, Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard where loose, sandy soils create unstable pressure that would cause straight walls to collapse. Curved walls form arches that are tightened by the pressure of sandy soil. The walls of the cellar retain extensive limewash, a material used to increase the reflected light and to sanitize the space since calcium hydroxide (the form which lime exists in limewash before carbonating into calcium carbonate) has a pH greater than 7 and kills numerous spores and bacteria before carbonating.

Frame

The main block of the house’s hardwood frame is nearly square and composed of two bays in width and two bays in depth (overall dimensions 26’-7” wide by 26’-10” deep). The narrower eastern bays are 11’ wide and contain a passageway, staircase and storage closet at the north end of the house with a longer room and fireplace at the south end. The western bays are 15’ wide; the northern bay is a parlor (14’-7” x 14’-7” interior dimension); the rear bay contains the central chimney in much of its northeast corner and a kitchen and passageway in the remaining space. The west side of the frame as a one-storey shed structure that tapers from a width of approximately 11’ at its façade (north elevation) to 4’-0” at its south end. Examination of the building’s frame during repairs in 2007 indicates that this shed is original to the structure, as western posts and studs of the house’s main block bore no signs of nail holes or scarring from exterior sheathing, nor did girts have empty pockets where studs would have existed if the shed were added. It is certain that the timber of which the frame was constructed was shipped to Nantucket, as building timber did not exist on island; it also seems likely that the frame was pre-fabricated on the mainland as part of a coastal trade in building frames. [Information needed.]

The south plate, sill and some joists had deteriorated and been spliced with modern materials prior to 2006. Following the partial collapse of the central chimney, these timbers were further damaged. Repairs to the sill, plate and joists in 2007 were made in-kind using full-dimension white oak timbers spliced into sound wood of the original frame.

Exterior

Original exterior claddings are not known. The building is currently covered with weathered wood shingles. Windows retain extensive early sash; however, plank frames appear to have been re-built in the 1990s to match the dimensions of the originals, but not reproducing original joinery.

Roof

Gambrel covered with modern wood shingle.

Interior

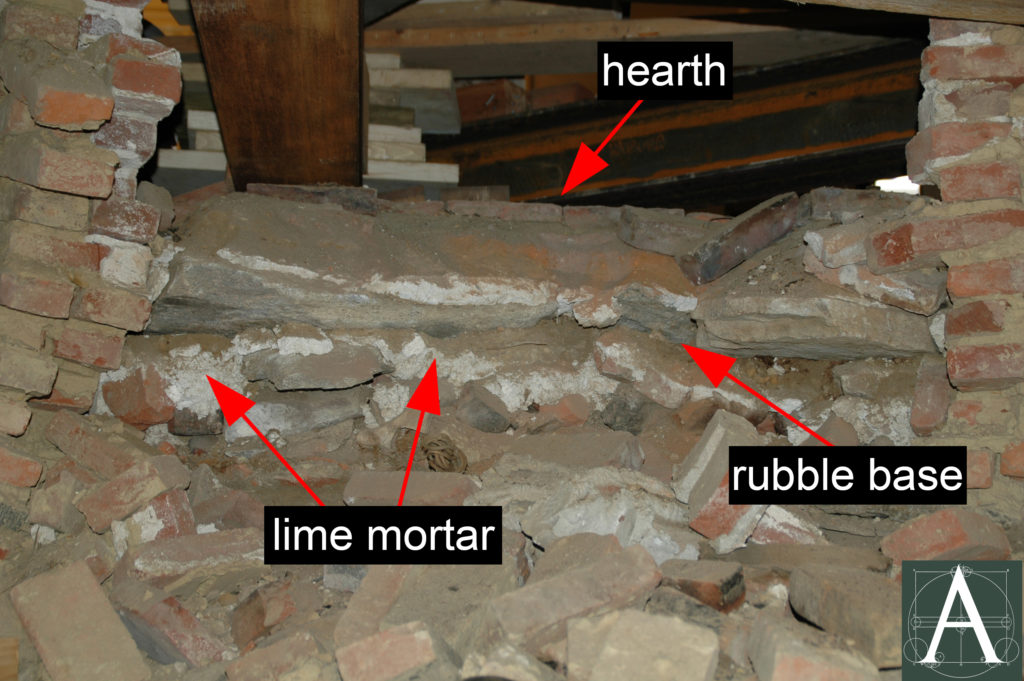

collapsed base of chimney seen from below showing rubble foundation laid roughly on grade in lime mortar

Built in the northeast corner of the house’s southwest bay, the central chimney stood on a base of rubble set directly on grade and daubed irregularly with lime mortar. Above its base, the chimney was originally laid in clay mortar. Hearths are supported by broad fieldstones extending from the chimney mass to wooden headers on which they rest; above the stone supports, the visible portions of hearths are made of bricks dry-laid in sand. Lime mortar was used at the exterior skin of the chimney where it was exposed to use or weather, specifically, at the faces of the fireboxes, exposed brickwork on the interior of the second storey and at the chimney cap above the roof. Original fireboxes possessed wooden lintels that were replaced at the first storey with wrought-iron lintels composed of two bars of iron each; however, at least one wooden lintel remains in position at the second-storey east fireplace.

In 2006, during construction of a new rear wing, the house’s central chimney was undermined by shifting subsoil, causing part of it to collapse into the structure. As a result, the rear plate which had been previously patched with modern 2”x 6” stock was broken by the collapsing masonry, the kitchen fireplace collapsed and the backs of the living room and dining room fireboxes collapsed. Second-storey fireboxes and the upper portions of the chimney survived perched atop a small column of masonry and held in position by surrounding timbers. Surviving elements were re-supported and retained in position. Caissons were dug around the collapsed subsoil to reduce the danger of further movement in the soil which exhibited broad fissures. Bricks, cranes, lintels, gudgeons and other elements of the collapsed fireboxes were retrieved from the cellar hole and used to reconstruct the partially collapsed fireplaces by bringing reconstruction brickwork up to meet the base of the surviving chimney stack. Bracing and reconstruction of the chimney was executed by Michael Burrey, preservation carpenter, in collaboration with Penelope Austin, lime plasterer/mason.

First and second storeys of the house retain extensive original finishes including walls of vertical sheathing trimmed with double-sided shadow mouldings, a finish that would have been somewhat old-fashioned on the mainland but which lingered on Nantucket well into the 1770s. In addition, the house retains most of its original lime plaster with a heavy buildup of limewash on its surface. Repairs to plaster were made in kind using high-calcium lime and hair plaster. Surfaces were cleaned of modern paints, loose and brittle limewash by steam cleaning and gentle scraping; however, areas of sound limewash were left in position. To assure that new coatings would retain the same permeability as original limewash, lime and casein paints were used on plaster during 2007 repairs.

First-storey finishes at southeast room showing shadow mouldings installed on sheathing over door heads.

The house also retains notable woodwork in the form of raised-panel doors, presumably original to its 1767 construction. These doors were repainted flamboyantly in the first or second quarters of the nineteenth century to appear as flame-grained veneers. Grained doors were conserved and re-waxed to protect finishes by Robert Mussey Associates, Inc., conservators.

Repairs to damaged hand-wrought hinges, door latches and re-fabrication of fireplace gudgeons and cranes to match documented originals was carried out by Newton Millham, blacksmith.

Contributor

Brian Pfeiffer, architectural historian; Penelope Austin, lime-plasterer & mason; Michael Burrey, preservation carpenter; excerpts of history taken from Ramblings, published by the Nantucket Preservation Trust.

Sources

Historic American Buildings Survey: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/hh/item/ma1664/

Nantucket Preservation Trust: “Master Mariners, Whaling Wives, and Tradesmen of the Whaling Era” Ramblings. http://www.nantucketpreservation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/WalkingTour.pdf