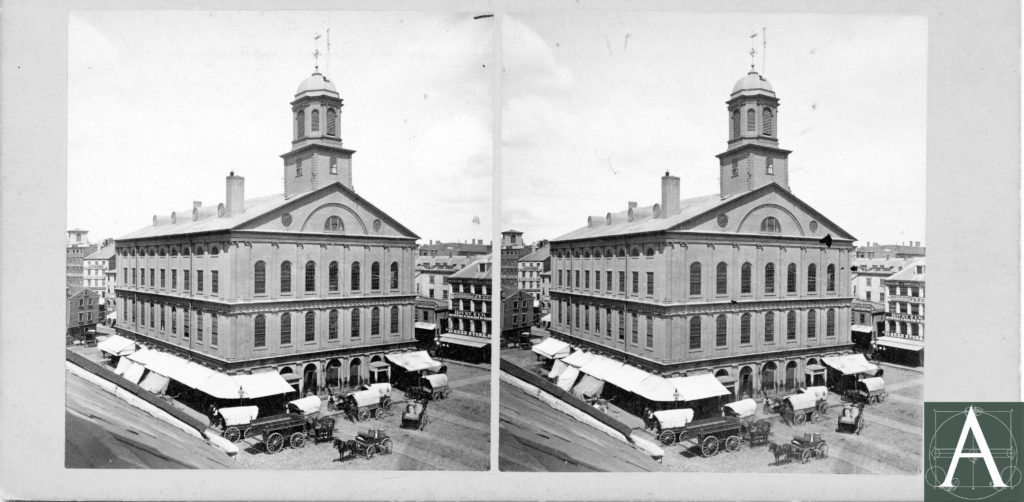

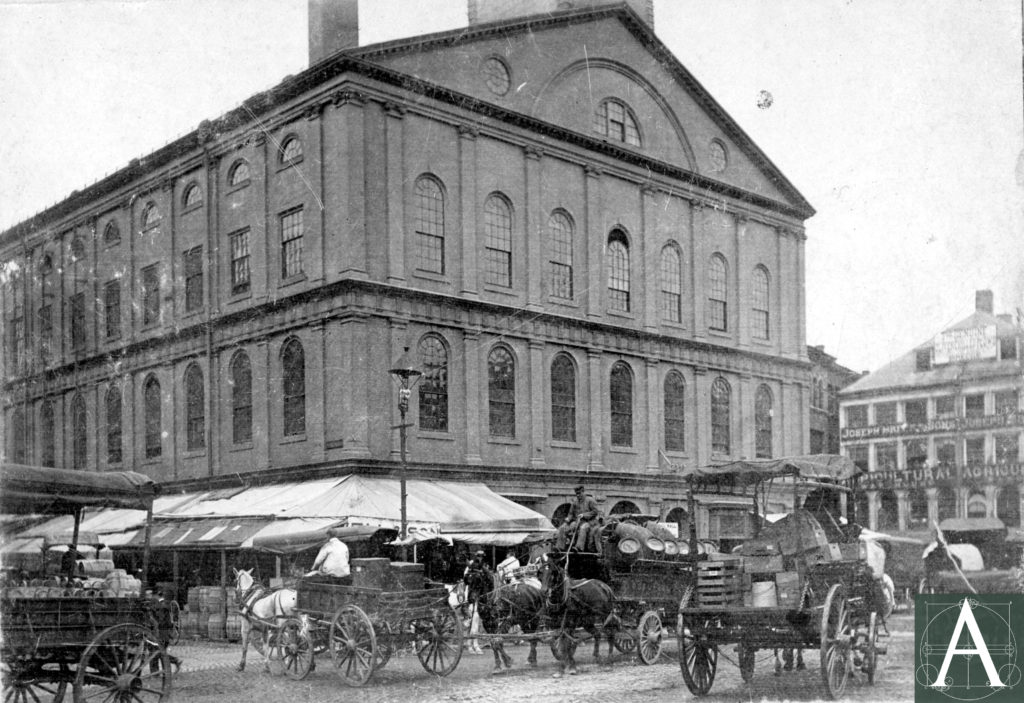

Faneuil Hall (ca. 1856), Dock Square, Boston, MA – one of the earliest views of the building showing a monochromatic color scheme [image courtesy of the Bostonian Society]

Notable Elements

- 18th- & early 19th-century masonry with a history of being painted [History & Exterior]

- Georgian & Federal-style interior finishes [Interior]

History

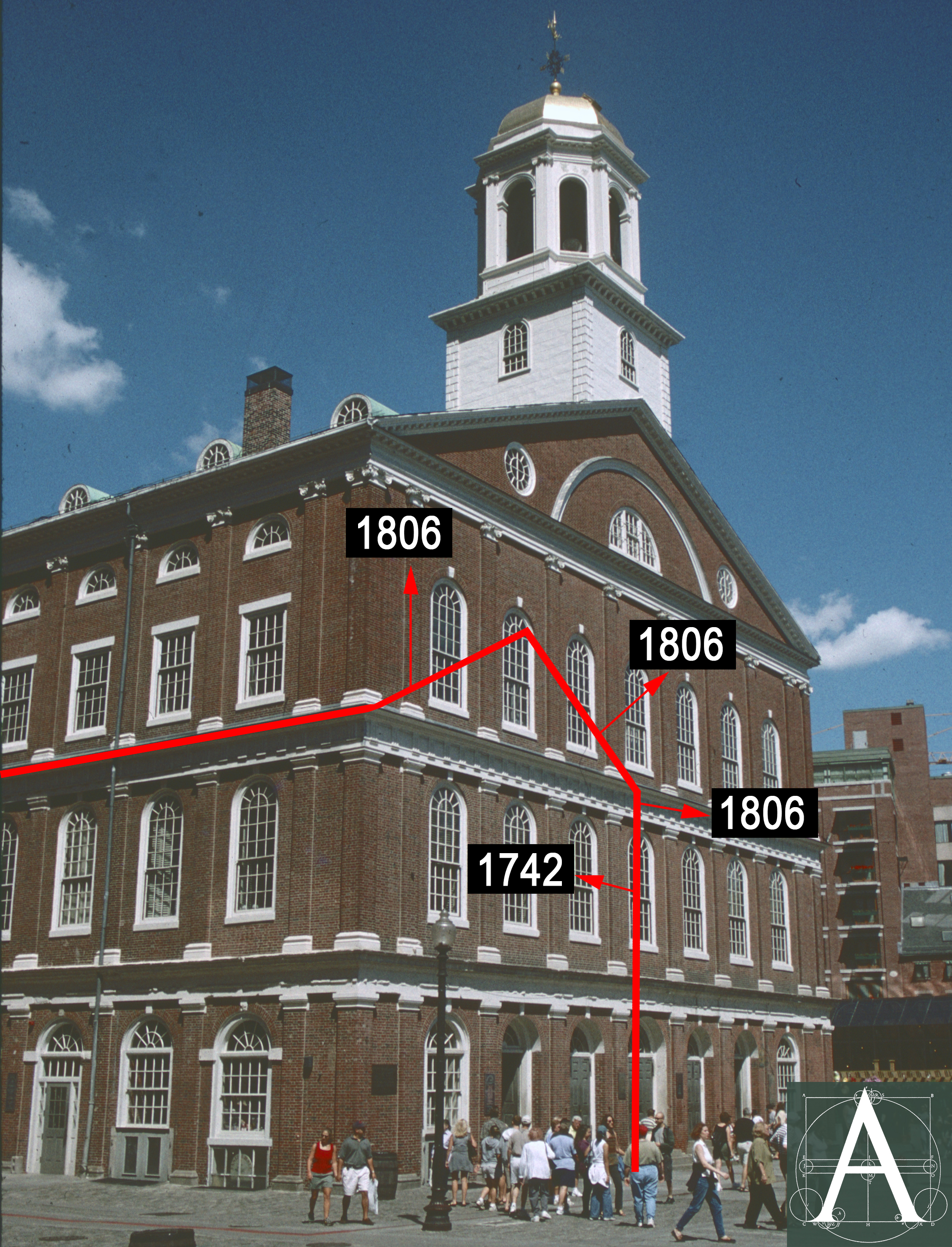

In addition to its significant social and political history, Faneuil Hall has a complex architectural history. The building was constructed as a market hall in 1741-42. Based upon information contained in an 1806 report from Charles Bulfinch, the original building was designed by the painter John Smibert, and was enlarged to two storeys during construction after the donor increased his gift to include a public meeting hall. As initially constructed, the building was 100’ long by 40’ wide and rose two stories to a pitched roof. The shell of this original structure is contained within the southern half of the present building’s first two storeys.

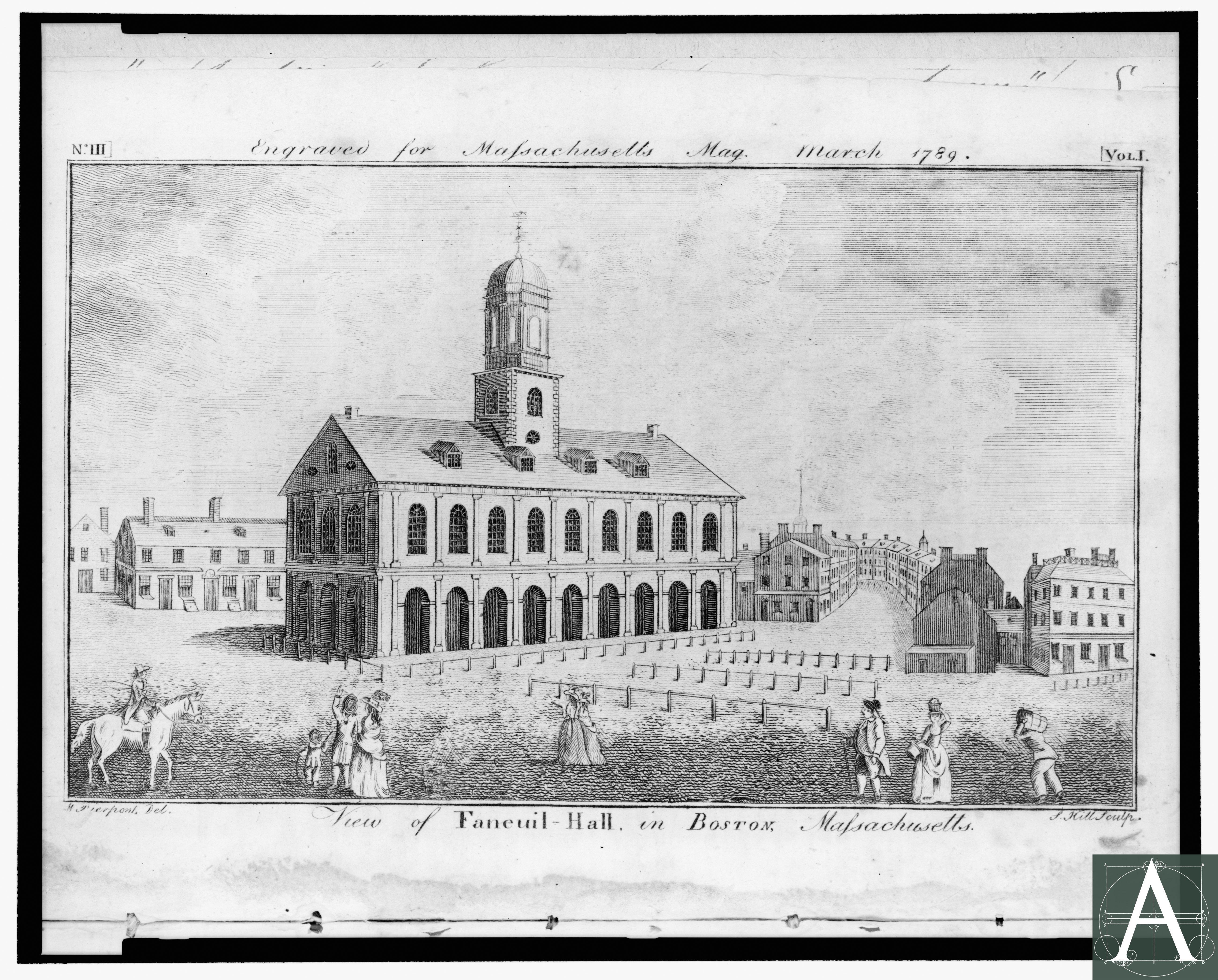

Faneuil Hall in 1789 before enlargement by Charles Bulfinch in 1806 [image courtesy of Library of Congress]

Faneuil Hall (2001) showing brick exposed by 1923 paint removal; dashed line traces the volume of the original 1742 building incorporated within the current structure

On January 14, 1761, the building burned completely, leaving only its brick shell standing. Contemporary reports speculated that the fire was hastened by the building’s wood (shingle) roof on which cinders could spread fire while neighboring buildings with slate roofs were protected from burning. Reconstruction of the building was undertaken with Thomas Dawes and, possibly, Governor Francis Bernard serving as architects. By October 7, 1762, the building was sufficiently complete to allow the resumption of Selectmen’s meetings in its hall. The original shell dictated the form of the building, but all other elements were new and probably appeared much as they were shown in a 1789 illustration published by the Massachusetts Magazine. It was in this form that the building achieved its political significance at the time of the American Revolution.

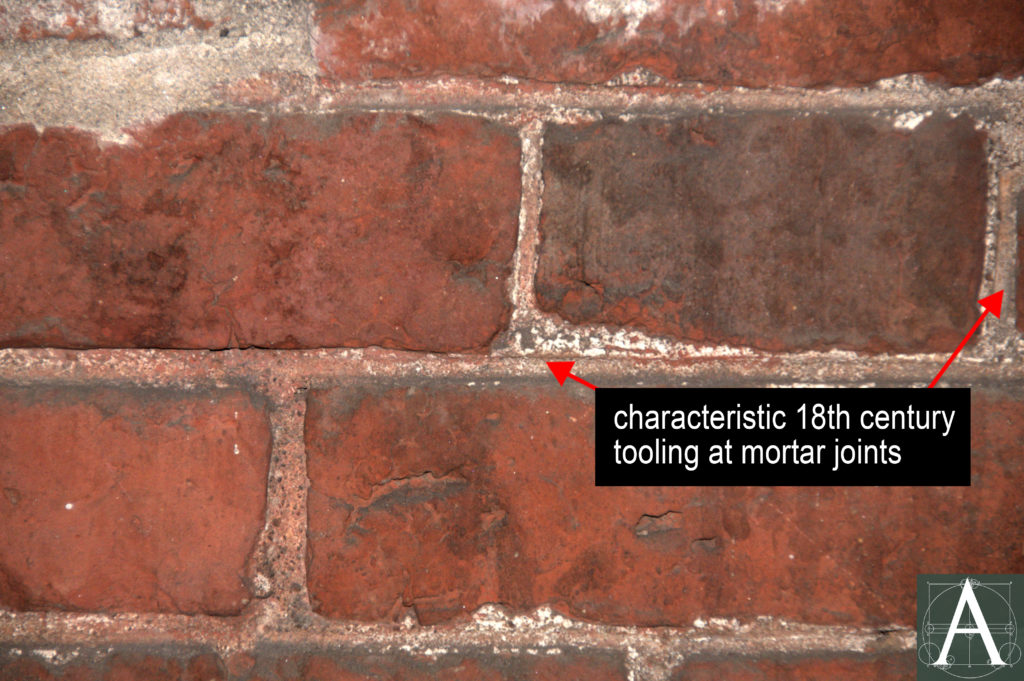

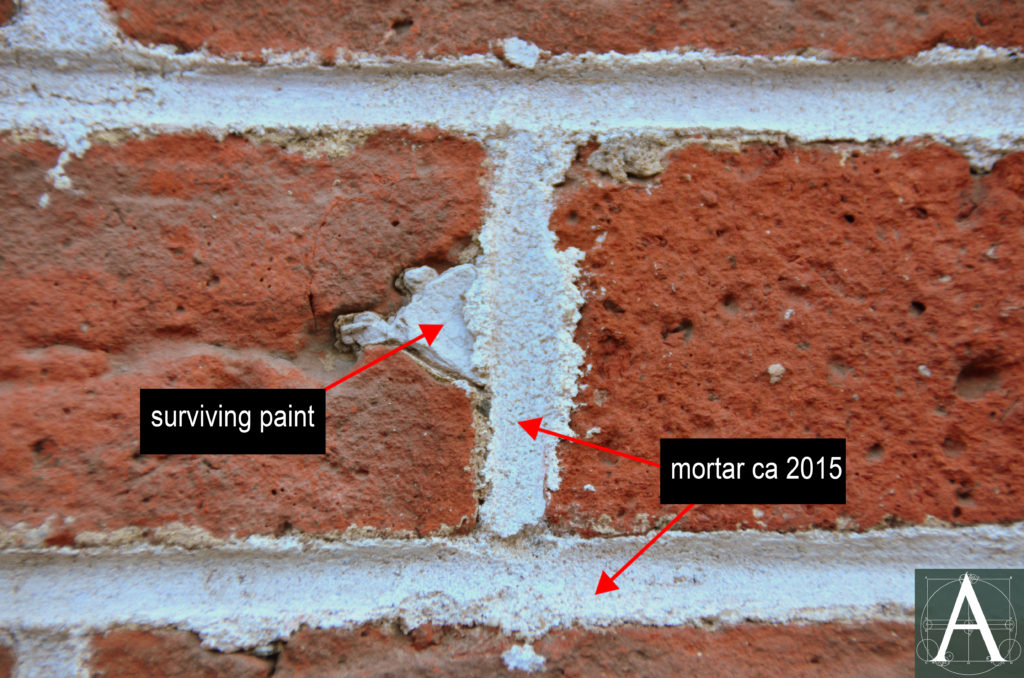

In 1791, Charles Bulfinch was appointed “to contract with some Person to Paint Faneuil Hall and he Selectmen’s Room, as early as possible…” [Boston Selectmen’s Minutes, 11 May, 1791, p. 150]. In 1799, Bulfinch and Thomas Tileston were appointed to consider the feasibility of underpinning Faneuil Hall to create a cellar, presumably for the storage of goods for commercial tenants on the ground floor. By 1805, the need to enlarge the structure had become apparent, and Charles Bulfinch developed a plan of enlargement that was accepted on May 23, 1805. Bulfinch’s plan quadrupled the size of the original building by doubling its footprint to 100’ x 80’ and nearly doubling its height. Bulfinch retained the classical pilasters and entablatures of the building’s original design and extended them northward onto the addition to make the two structures into a unified design. The building’s current appearance largely dates from this period of construction with the exception of the now-exposed red brick, which were probably painted to provide a uniform exterior color [see Exterior below].

In 1898, after twenty-four years’ debate about fire safety in Faneuil Hall, the building underwent a major reconstruction. Interior wood framing was removed, as was the wooden roof structure, and replaced with steel and concrete structural supports. Original woodwork was removed; sections were re-installed with their original materials; however, many columns, door cases, balusters and other wood elements were replaced with metal copies to reduce flammability. Plaster walls and ornamental work were removed and replaced with modified versions of the original features in places where room dimensions were changed.

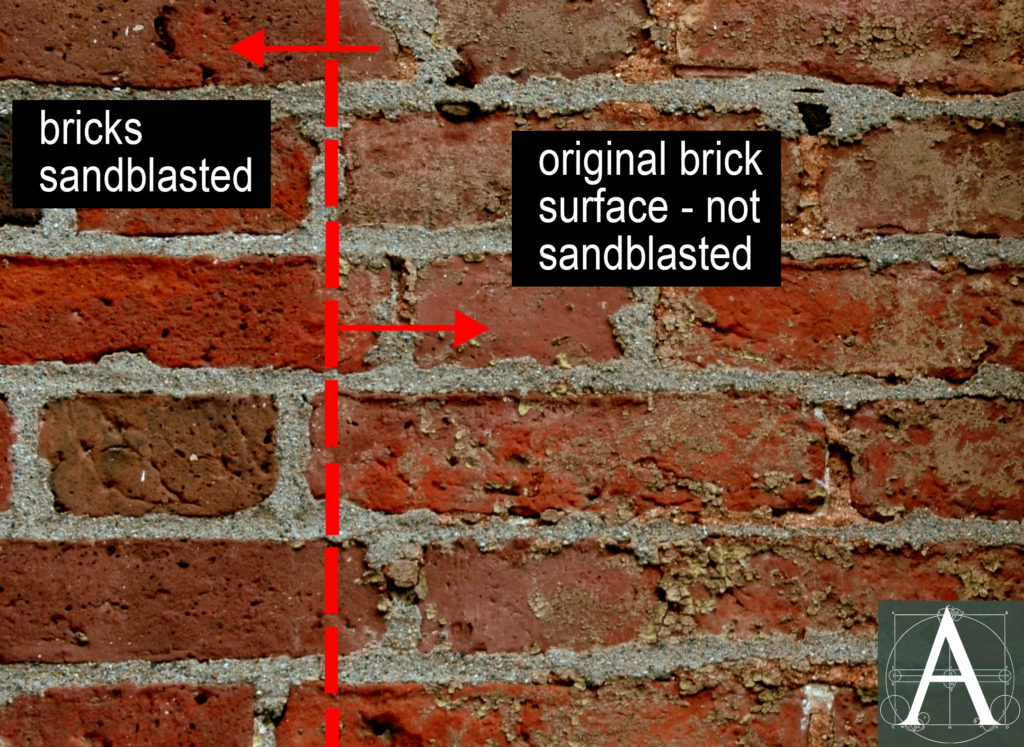

In the early twentieth century, calls for improving the building continued with Mayor James Curley proposing “to repaint it [Faneuil Hall] outside and inside, as well as to remove the unsightly coat of paint which covers the brick walls.” This proposal was supported by the Boston Society of Architects, which recommended “that the outside walls be treated with sandblast to remove all paint and to restore the bricks to their color of (1742)…” [see Exterior below]. Some work was carried out in 1911-12 but was suspended until 1923-24 when it resumed under the supervision of Ralph Adams Cram, architect, and Frank Chouteau Brown, consulting architect.

Dates

1741-42; 1761-62; 1806; 1827; 1898-99; ; 1911-2-12; 1923-24

Builder/Architect

- 1741: John Smibert, Architect – attribution from Charles Bulfinch in report with 1806 drawings

- John Blanchard, Mastermason [sic.] & Samuel Ruggles, Builder

- 1761: Thomas Dawes, Bricklayer & Architect

- Governor Francis Bernard, Amateur Architect associated with Thomas Dawes

- Samuel Ruggles, Builder

- Hans Christian Geyer (also Geer), Stonecutter

- 1806: Charles Bulfinch, Architect

- Jonathan Hunnewell, Mason/Bricklayer – primary builder for enlargement

- 1898: Frank W. Howard, Chief Architect

- Francis W. Chandler, Consulting Architect

- Arthur E. Anderson, Supervising Architect

- Woodbury & Leighton, Builders

- 1923: Ralph Adams Cram, Architect

- Frank Chouteau Brown, Consulting Architect

Building Type

Market Hall with former stalls at ground floor and public offices/meeting halls at upper floors

Foundation

Granite rubble – underpinned 1799(?) to create a cellar [Information needed.]

Frame

The structure originally contained wood framing within masonry bearing walls. Wooden structural elements were removed and replaced with steel and concrete in 1898.

Exterior

Faneuil Hall (ca. 1856) oblique view showing monochromatic color scheme and struck joints [image courtesy of the Bostonian Society]

By the fourth quarter of the twentieth century, many of these monuments, including Faneuil Hall, began to be the subjects of more careful, research-based historic structure reports that sought to document the buildings’ evolutions using both written records and scientific analysis of physical evidence. These reports frequently note the one-time presence of coatings, but often conclude that they were a later addition, based upon the documentary record in which subsequent repaintings of public buildings are recorded. This stress on the documentary record may bias the findings against a practice that was considered too ordinary a part of building and finishing masonry buildings to warrant separate itemization in building contracts and plans. Additional building archaeology and analysis of remaining evidence on historic building is needed to document the original finishes of these important buildings.

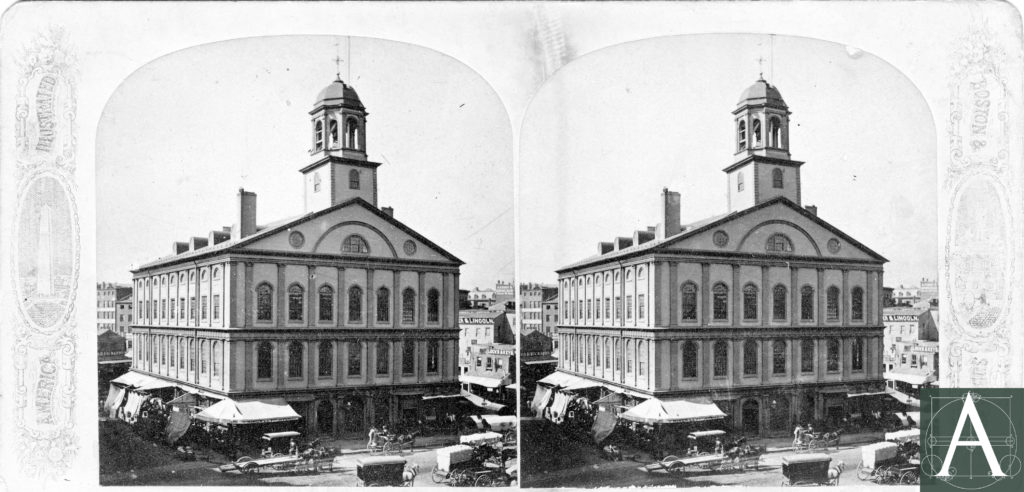

Faneuil Hall (ca. 1870-80) view of two-color scheme in which the body is a light color and classical trimmings are picked out in a darker color [image courtesy of the Bostonian Society]

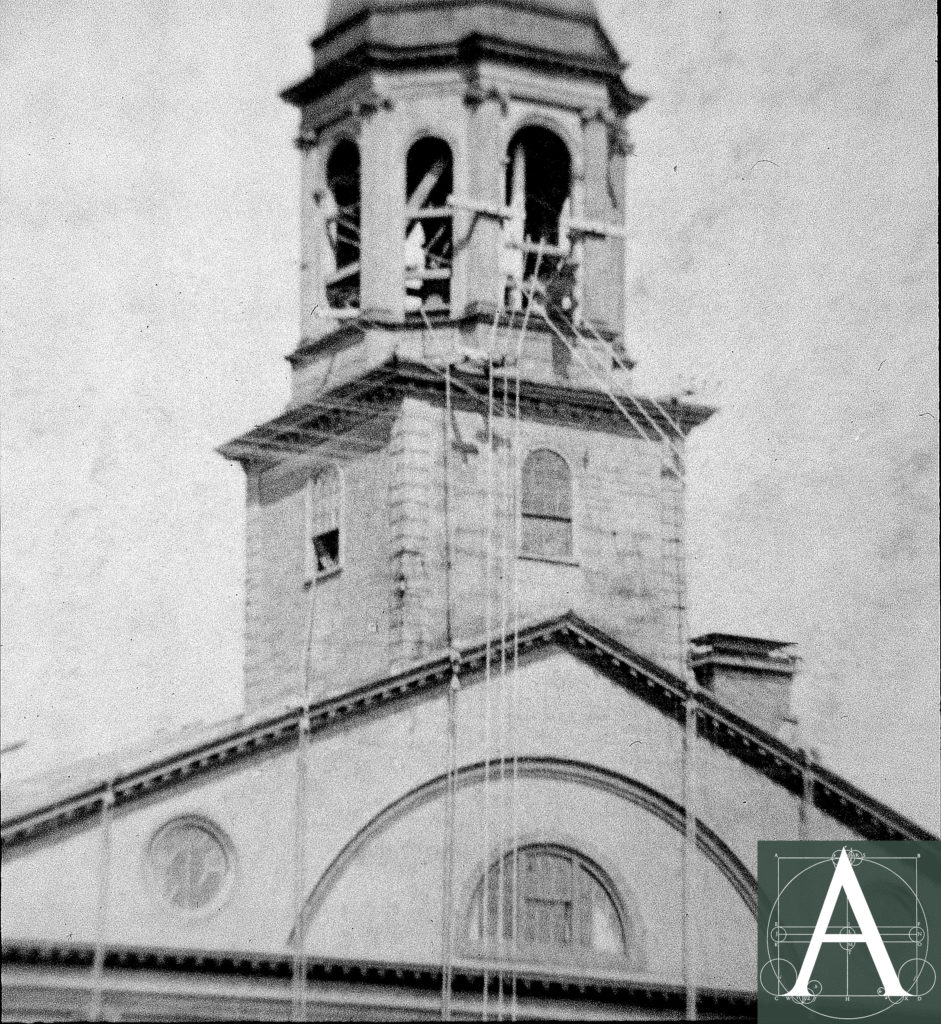

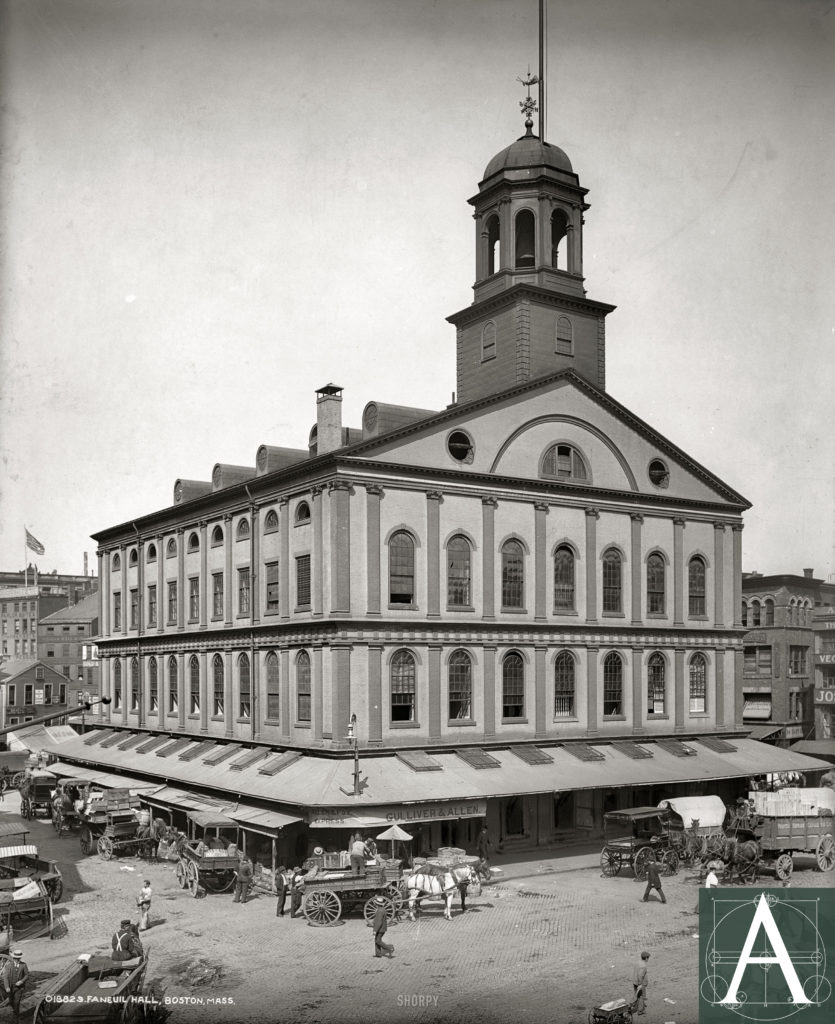

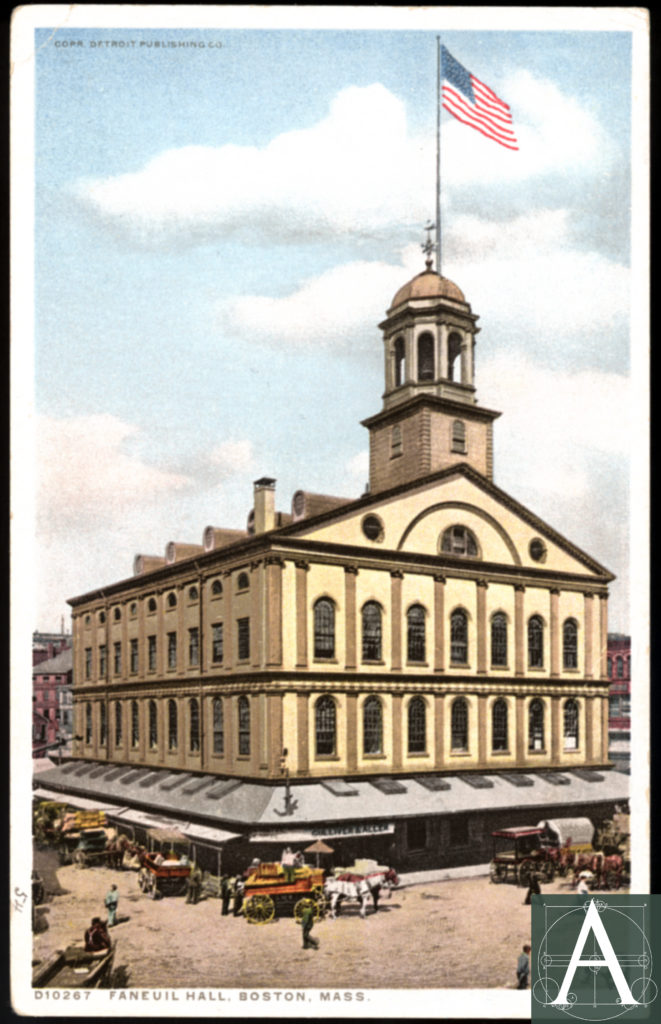

Photographic sources show that the building had been painted with contrasting colors by 1879 with pilasters and entablatures painted darker than the body of the structure. In 1881, architect Charles Cummings criticized the 1806 enlargement of the building, stating that “a certain blankness and monotony of effect was the result which did not belong to the old hall, and which has not been ameliorated by painting the walls a dusty brown color.” (Detwiller, p. 35.) At approximately the same time, historic photographs show the building covered with swing staging and scaffolding for painters who may have added another layer of contrasting paints shown in a postcard view of ca. 1916-24. While postcard companies sent artists out to record the colors of buildings that were photographed in black and white, and colored during the printing, they also took liberties with the original colors. With buildings such as the Old Corner Bookstore (1719 – 227 Washington Street, Boston, Massachusetts), postcards from the same photograph and same company show the building variously as red or ochre.

Faneuil Hall (ca. 1890) probable view of dark monochromatic color scheme described by Charles Cummings, architect, as a “dusty brown color” in 1881 [image courtesy of the Bostonian Society]

Faneuil Hall (ca. 1890) detail of painters on swing staging repainting the exterior [image courtesy of Historic New England]

Faneuil Hall (1903) last phase of exterior paint (?) with a contrasting color scheme between the body of the structure and its classical style trimmings [image courtesy of Shorpy Historic Photo Archive]

Faneuil Hall (1916-24) colored postcard view with last coat of paint before paint removal carried out [Image courtesy of the Bostonian Society]

The 1987 supplementary Historic Structure Report for the building concluded that masonry walls were in stable condition and did not require painting to protect it. It did note that “Repainting the brickwork would restore it to a pre-1923 appearance and there are no compelling reasons to take that approach at this time.” (Goody-Clancy, pp. II-9 & II-10.)

Even if the exterior of Faneuil Hall is not in need of immediate repair or coating, the iconic importance of the building warrants an investigation of fragile paint evidence before it is lost, to determine more precisely its accurate original appearance and the role played by exterior painting as a possible original element of the building’s classical design.

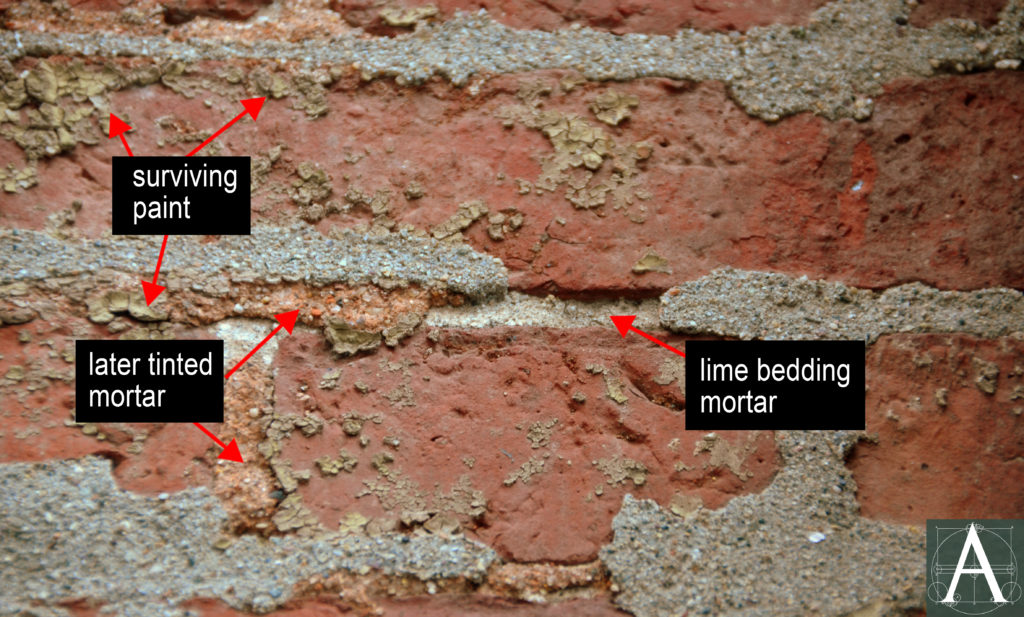

Faneuil Hall – south elevation showing surviving layers of paint and undamaged original brick surfaces in an area protected from sandblasting by a sign

Faneuil Hall – close-up view of undamaged brick surfaces and surviving layers of paint on protected area of south elevation

Derby House, Salem, Massachusetts – view of 1762 masonry with original struck joints and surfaces from 1762 protected from weather by an addition (ca. 1810)

Faneuil Hall – masonry at north elevation showing a close up of modern mortar composed of hydrated lime and Portland cement; built-up layers of paint survive in brick crevices

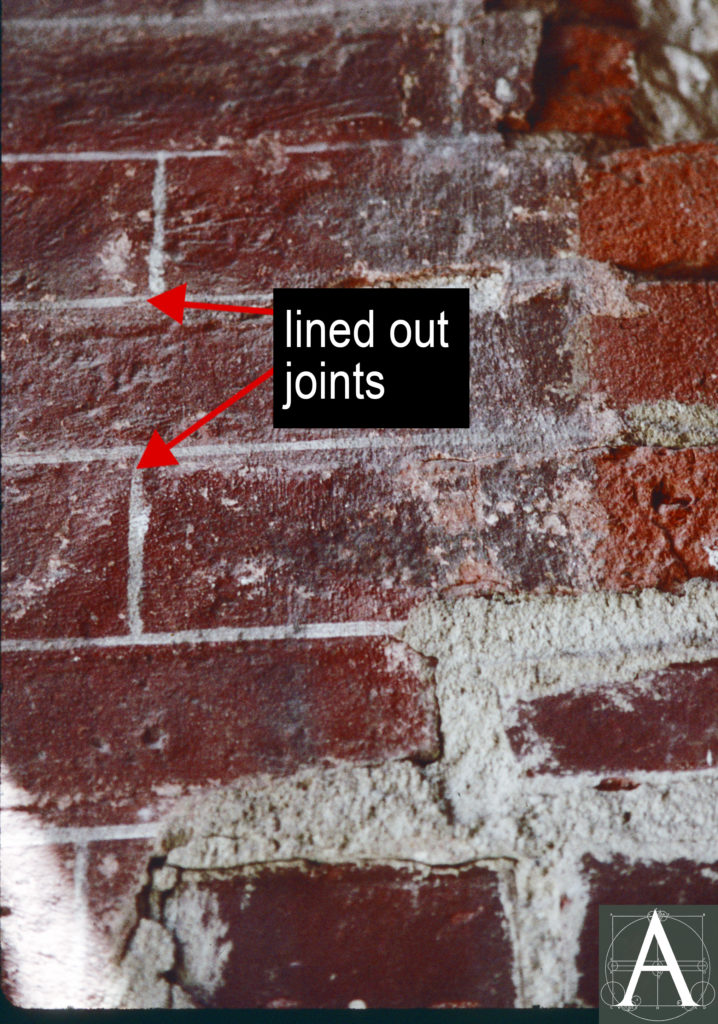

Faneuil Hall – lined-out mortar joints and tinted/painted surfaces (ca. 1827) on the underside of ground-floor arches at the south elevation

Roof

Based upon a contemporaneous newspaper report of the 1761 fire, the original roof was wood shingles on wood sheathing and a wooden structure. It is unclear if the roof was replaced with a slate-covered roof in the reconstruction that followed in 1761-62. Following its 1805-06 enlargement, the building may once again have been covered with wood shingles, as the roof was found to be in poor condition and needing new covering as early as 1819, only thirteen years after completion. In 1898, the entire wooden roof structure was removed and replaced with a steel frame covered with slate.

Interior

The building’s interior was substantially rebuilt in 1898-99 by the removal of all its structural elements, which were replaced with steel and concrete to render the building fireproof. In the process, many of the original wooden trimmings were re-set, but many were replaced with facsimiles made of metal or other fireproof materials. A summary analysis of surviving elements can be found in Historic Structure Report: Faneuil Hall, Boston, Massachusetts by Frederic Detwiller, pp. 71-82.

Contributor

Brian Pfeiffer, architectural historian & editor, information excerpted primarily from Historic Structure Report: Faneuil Hall, Boston, Massachusetts by Frederic Detwiller, and from direct examination of the structure.

Sources

Detwiller, Frederic C. Historic Structure Report: Faneuil Hall, Boston, Massachusetts. Boston: National Park Service, 1977. At the Bostonian Society: call number F 73.8 .F2 D4 [OVER]

Goody, Clancy Architects. Faneuil Hall Historic Structure Report – Supplementary Report. Boston: National Park Service, 1987. At the Bostonian Society: collection – MP0001;Item Nbr:1990.003.

Historic American Buildings Survey http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/hh/item/ma0902/

Library of Congress 1789 Image of Faneuil Hall http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3a45763/

Shorpy Historic Photo Archive http://www.shorpy.com/Faneuil-Hall-Boston

Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities. “Thomas Dawes: Boston’s Patriot Architect,” in Old-Time New England 68, No. 249 (Summer/Fall, 1977): 1-18.