Notable Elements

Notable Elements

- Early masonry construction with lime mortar [Exterior]

- Clay mortars and renders [Interior]

- Evidence of an early/original rear ell [Exterior]

- Large kitchen hearth & supporting arches [Interior]

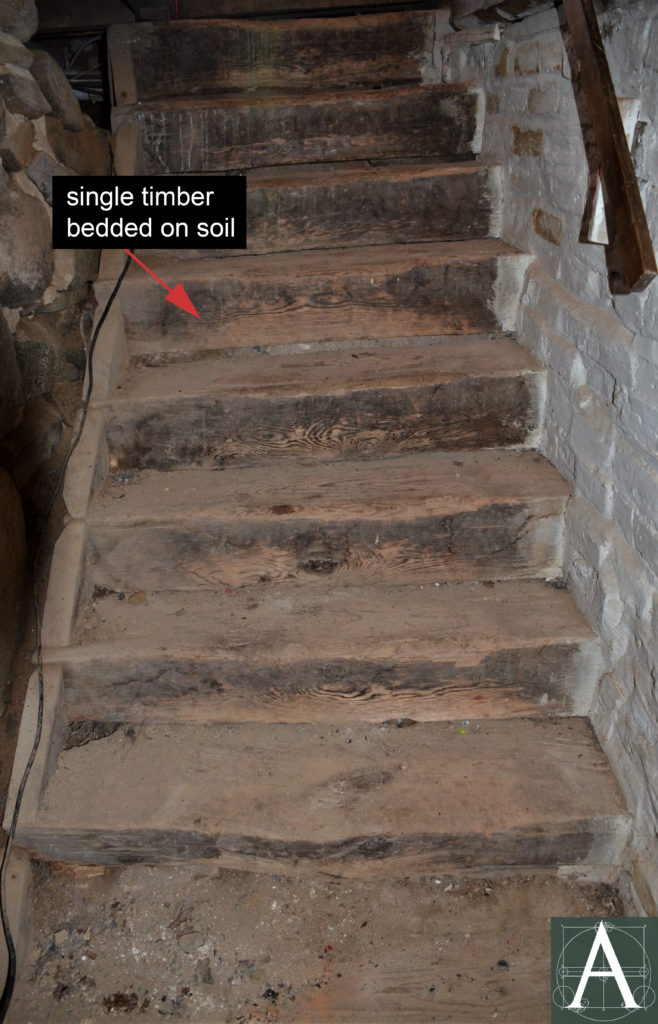

- Puncheon stairs to cellar [Interior]

History

The Samuel Weeks House is a rare early example of masonry construction in New England. The region’s lack of building lime (an essential ingredient in traditional mortars) increased the cost of masonry construction. Combined with the region’s abundant supplies of wood, timber-frame architecture predominated and only a small number of brick houses were built prior the second half of the eighteenth century. Located in a rural setting, the Weeks House was certainly among the most ambitious and expensive houses in its town at the time of its construction and for many years after. Despite the house’s local prominence, documentation is sparse. A few early references and archaeologically interesting elements of the building help to discern the building’s original appearance and the various changes made to it over the course of three hundred years.

Like a number of other early masonry houses, the Weeks House was romanticized in local folklore in the late nineteenth century. The house was believed by some and even published in histories as having been built in 1638 as a defensive garrison house. Later genealogical research and rereading of public records indicates that it was built not by Leonard Weikes (Weeks), an English settler who did not arrive in New England until 1639, but more probably by his son, Samuel Weeks (1670-1746) whose maternal grandfather, Samuel Haines, was the first settler of Greenland in 1635 and its largest landowner. The Samuel Weeks House may have been confused with his father’s house from a 1663 reference to a “…hiwaye lade out over against Leonard Weikes house…” Family tradition reported that Leonard Weeks’s house was incorporated into Samuel Weeks’s house as the original rear ell for which there is physical evidence on the rear elevation. [see Exterior] The house remained in the Weeks family through nine generations until 1968. Seven years later, in 1975, it was purchased for preservation purposes by Leonard Weeks & Descendants in America, Inc. together with thirty-three acres of land.

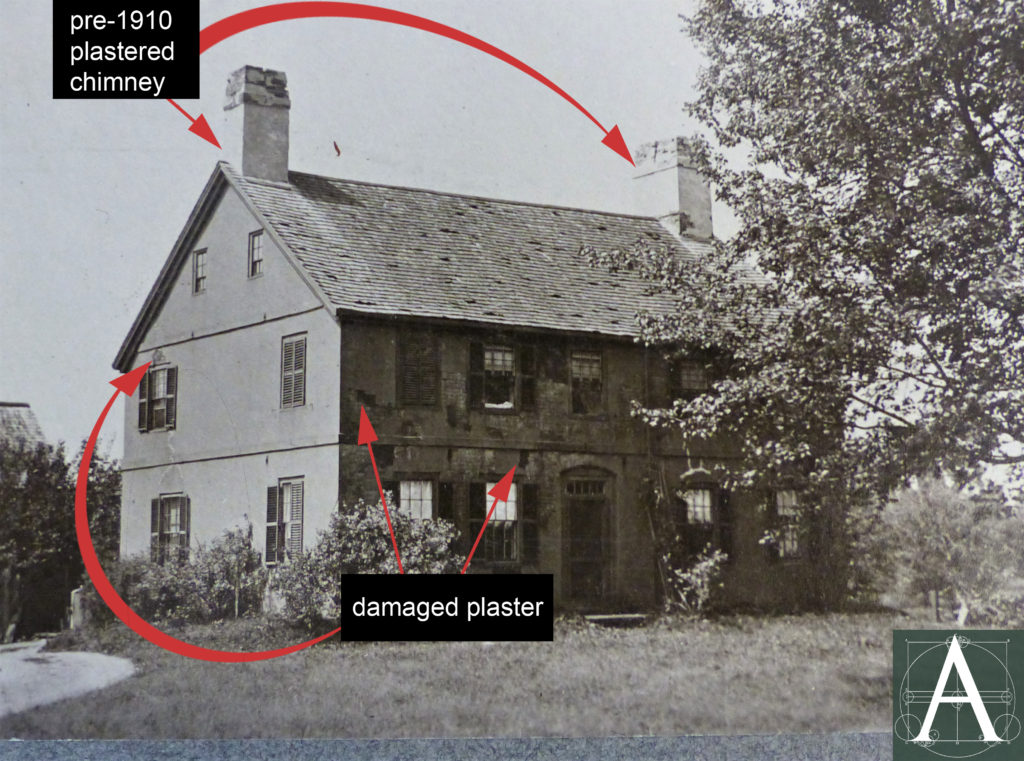

- Frederick Kelly (1888-1947), a well-known restoration architect visited the house in 1940-42 and donated several photographs to the Archives of Historic New England, including a couple earlier views that he acquired from third parties. It is not clear if he visited out of personal curiosity or as an architectural advisor for the removal of exterior plaster and restoration. Kelly’s papers at the Whitney Library of the New Haven Museum contain no references to the project in MSS-270, Folders 3/A and 3/H.

Samuel Weeks House, pre-1940 showing deteriorated plaster that once covered house [image #19349A courtesy of Historic New England]

Date

1710

Builder/Architect

Unknown

Building Type

Single-family residence:

Measuring 41‘-10” across its façade by 28’-10” in depth, the Weeks House bears similarity to the contemporaneous William Dummer Mansion House (1712-15) in Byfield, Massachusetts, which measures 44’- 6” across its façade and 29’-3” in depth. Both houses served as the centers of large landholdings and shared similar floor plans consisting of a central hallway with two small rooms sharing a single end-wall chimney stack on one side, and a large kitchen hearth supported on two arches at the cellar on the other side of the house. The base of the kitchen hearth at the Weeks House is 14’-0” x 4’-6” while that at the Dummer House is 16’-0” x 4’-6”. Despite similarity of scale and plan, the two houses are dramatically different in their architectural ambitions and social purposes. The Weeks House is a provincial example of a prosperous farmer’s house with relatively narrow passages, small doorways, and lower ceiling heights. The Dummer House is a fully developed Georgian-style country seat designed for a Royal Governor and his wife who were childless and occupied the house part-time. The façade is decorated with elaborately carved classical details, and the interior contains a small number of finely finished spaces including a broad staircase with turned balusters, paneled sitting room with casement shutters, tall door cases with eight-panel doors, and clear ceiling heights of 9’-8” at the first floor and 9’-5” at the second.

Foundation

Puncheon stairs at the cellar with a brick partition set atop the cantilevered treads and rubble-stone foundation visible in the background

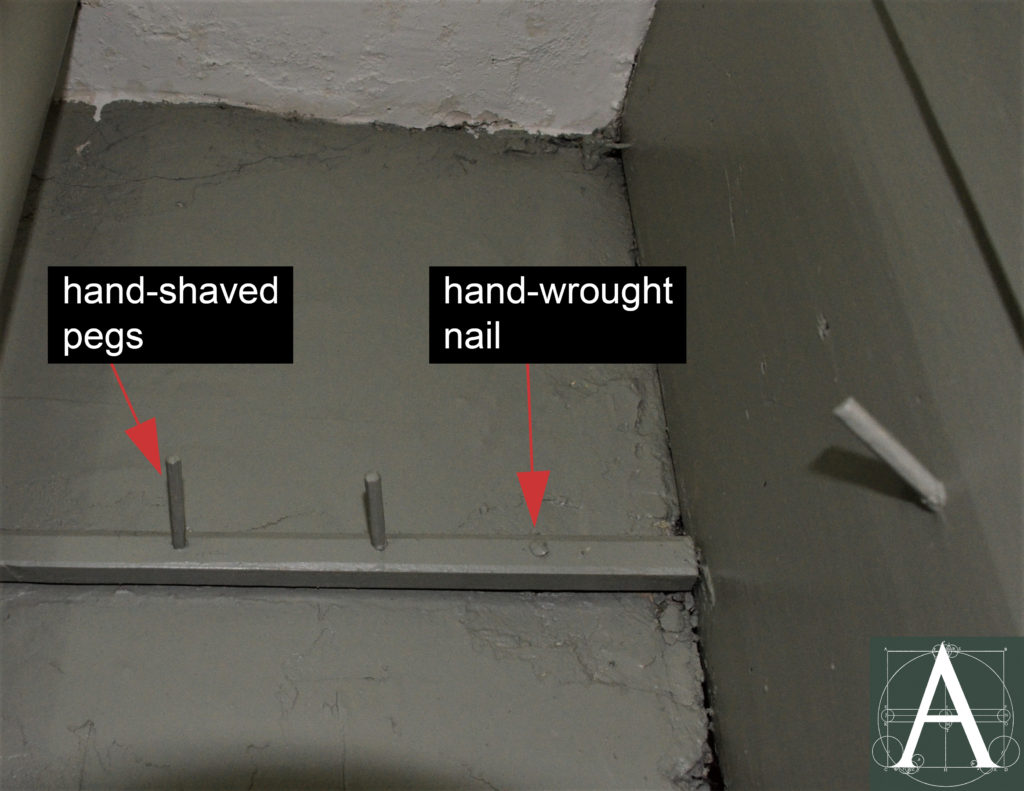

The house stands on a foundation of rubble stone below grade with brick starting at grade level. Like many other First Period houses, the Weeks House has only a half cellar beneath its eastern half; the western half has a crawl space with a dirt floor. The cellar had two entries: a bulkhead on its east elevation that led to a passage beneath the southern arch at the base of the kitchen hearth, and a puncheon stair from the first floor. The bulkhead is now closed with masonry, leaving the puncheon stair as the only access. Composed of large squared logs bedded directly on soil, the puncheon stair has a wall of rubble fieldstone on its west side and a brick partition set on the slightly cantilevered east ends of stair treads. The brick partition is laid with thin wood sleepers every second or third course, roughly aligned with the tops of the treads.

Frame

The house is framed with timber-frame elements characteristic of its period. First-floor framing visible in the cellar consists of 9” undressed timbers with bark set into 8” x 8” and 9” x 9” girts. Framing at the first and second storeys is concealed by plaster finishes. The attic floor is framed by 10-½” x 10-½” girts with 2” x 10-½” joists. The existing attic stair is set between two closely placed girts and appears to be in its original position. Roof framing consists of four unevenly spaced rafters (6-¼” x 5-¾”) with purlins (4” x 5-½”). Many original framing members bear char marks from a 1938 fire; sheathing and some purlins were replaced after the fire. The stair railing that encloses the head of the attic stair is fastened with hand wrought nails, indicating eighteenth-century origin. Similarly, a ladder/stair survives in partially charred condition; the roof hatch to which it once led has been removed and its opening sheathed over.

Exterior

Looking closely at masonry evidence:

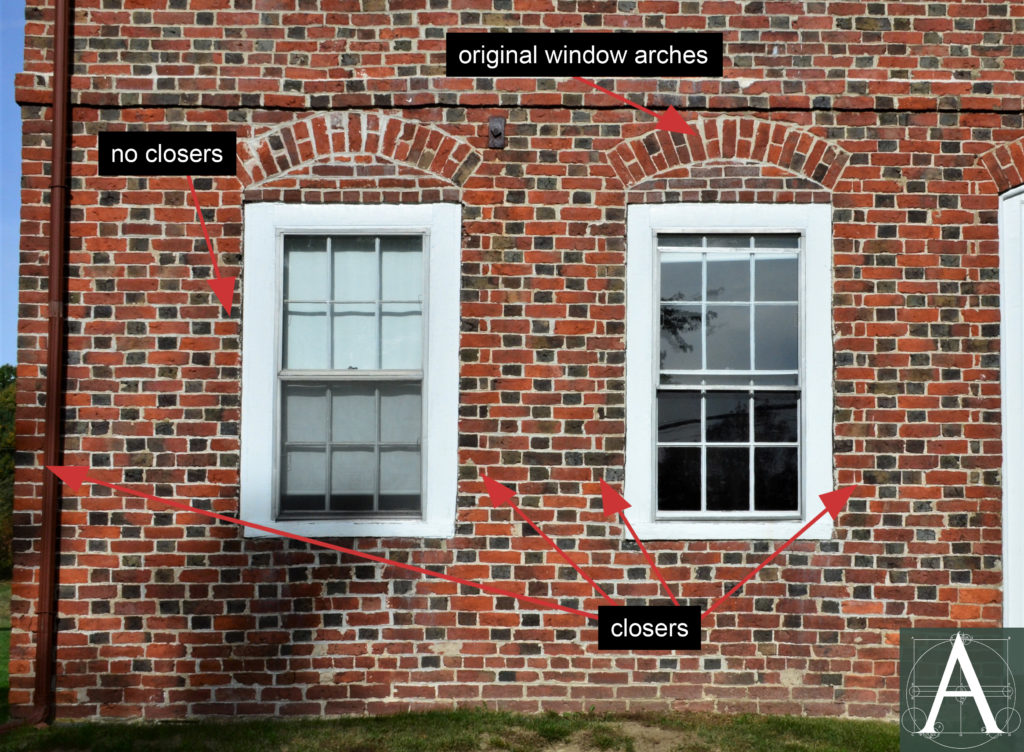

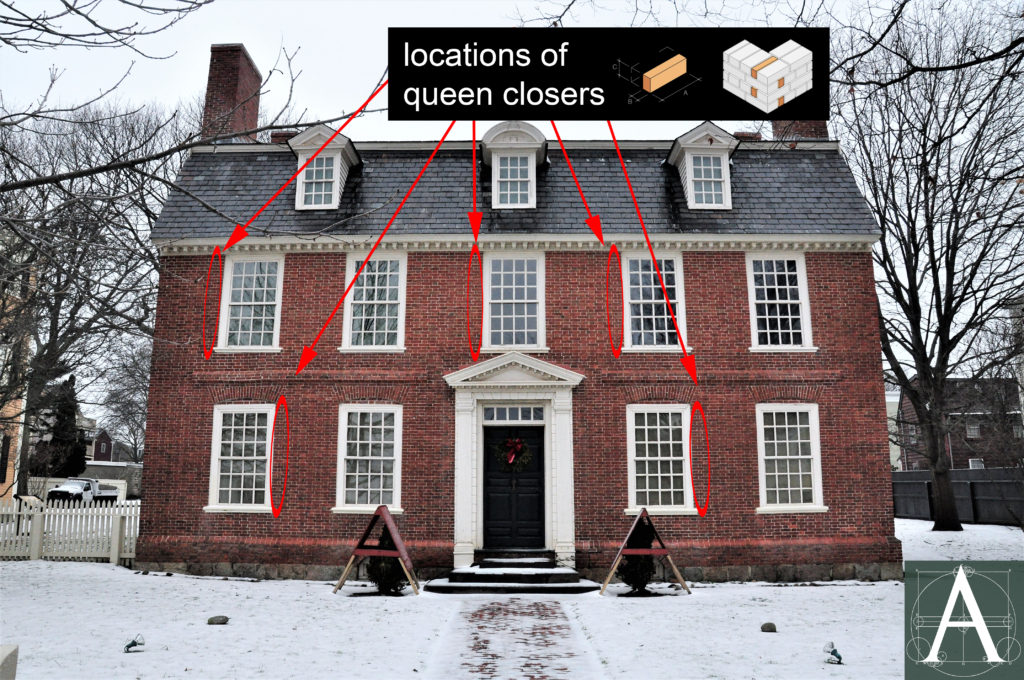

The house’s exterior follows patterns seen in at least two other houses of similar date, the Dustin Garrison House (c. 1700) in Haverhill, Massachusetts, and the MacPhaedris-Warner House (1716-18) nearby in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. All three are constructed of brick with façades laid in Flemish bond with blackened headers, and all three make use of queen closer bricks at windows and doors, but not in the symmetrical manner of high-style Georgian architecture such as Westover (1726) in Charles City, Virginia, where each window and building corners are neatly fitted with queen closers to maintain the vertical alignment of joints in the walls’ Flemish bonding. This irregularity of spacing might suggest that the façades were intended to be coated, as so many masonry buildings were in the eighteenth century (see Historic Masonry Finishes), except that the prominent use of blackened headers on each building occurs only at the façade (also the side elevation at the Dustin Garrison) and is highly intentional, suggesting it was originally left exposed, even if side elevations laid in common bond were coated.

Façade (south elevation) showing Flemish bond brickwork with blackened header; chimney caps rebuilt ca. 1910-20 (?)

Masonry details at the façade showing irregular installation of queen closers at window surrounds and building corners

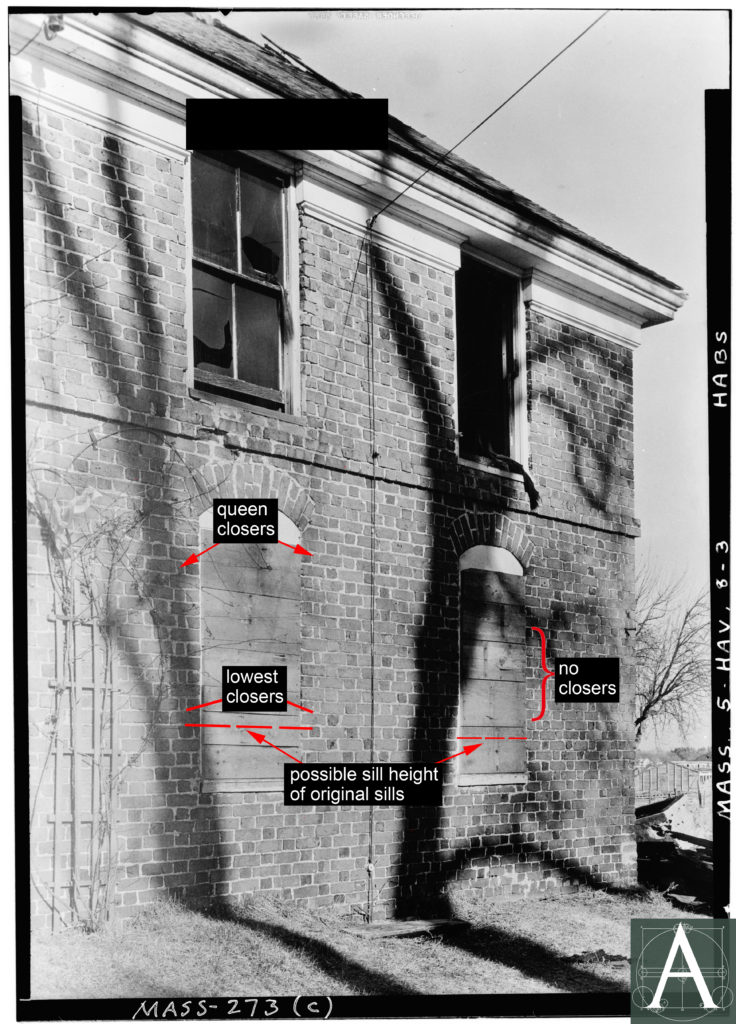

Masonry details at the Dustin Garrison House, Haverhill, Massachusetts (ca. 1700) showing irregular installation of queen closers at window surrounds and possible original window sill heights that resemble the Weeks House [HABS, Arthur C. Haskell, photographer]

The façade of the Weeks House is slightly asymmetrical in a manner characteristic of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The eastern half of the house, which contains a large kitchen hearth and, presumably, the house’s most actively used room, is wider than the west, which was divided into two small rooms. Queen closers occur on the jambs of some window and door openings but do not extend to the current window sills; instead, they stop four courses above. Even at the front door jamb, closers stop at the same level. It is unclear if this treatment indicates that windows were once shorter and their sills higher, or if variable brick sizes required these closers to maintain the vertical alignment of joints of the Flemish bond. The same condition exists at the ground-floor windows of the Dustin Garrison House where queen closers cease six courses above the window sills.

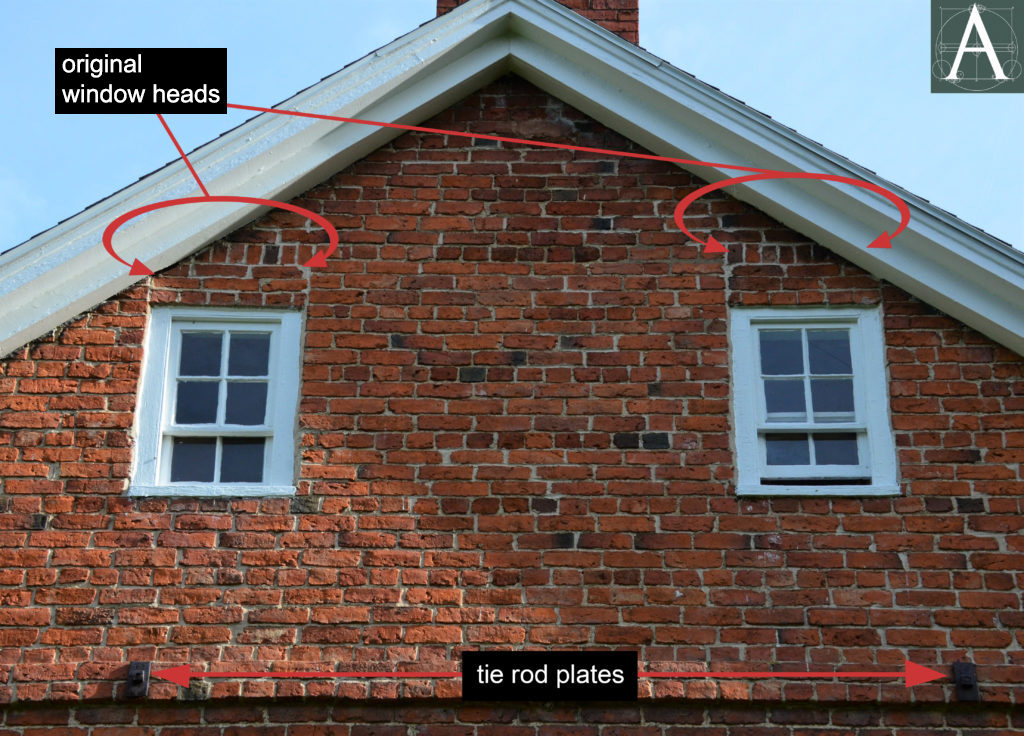

The house’s side elevations bear simpler details than the façade. They are laid in common bond (3 courses of stretcher per course of headers that tie the layers of the wall together); blackened headers are few and randomly scattered. Each gable end has two tie-rod plates at the heads of the first and second stories to hold wood framing and masonry securely in position. Settlement cracks in the walls, especially at the building’s southeast corner, support the tradition that these wrought-iron ties were introduced following the Earthquake of 1755 that caused cracks in the house.

Window openings on side elevations have been widened and enlarged from their original dimensions. On the west elevation, the narrow arches of first-storey windows stand above wider openings that were probably cut by the beginning of the nineteenth century to allow the installation of larger double-hung sash. At upper floors of the gable ends, flat arches of headers exist at the center of window heads marking the width and placement of original windows at both the second storey and attic.

Side (west elevation) close-up of ground-floor window surround showing old-flat arch head of the original, narrower window

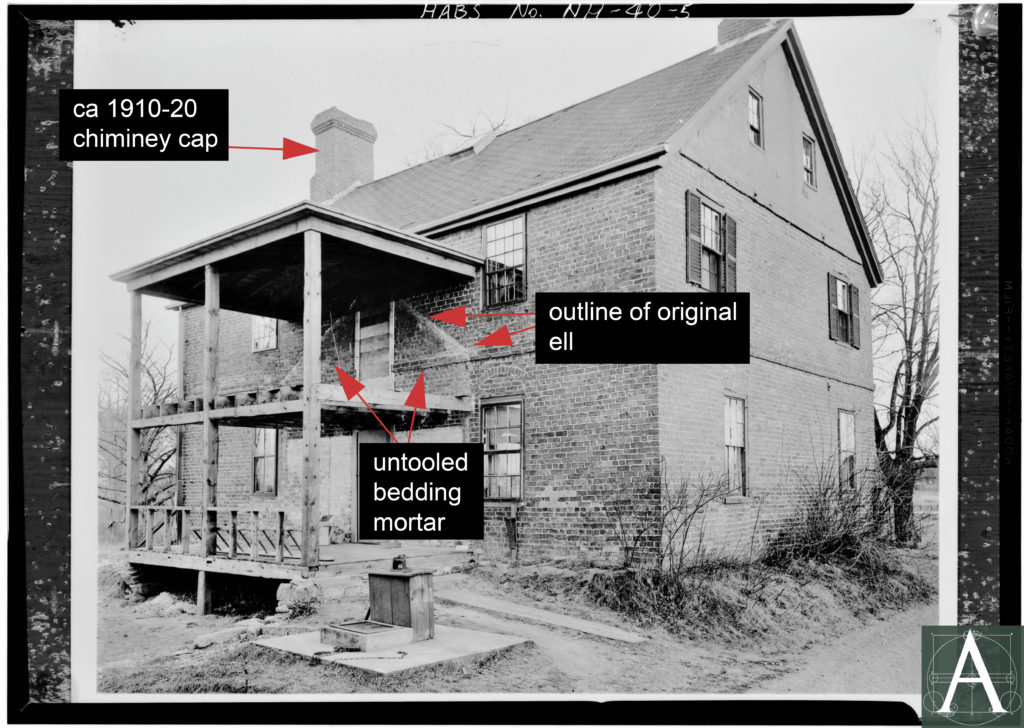

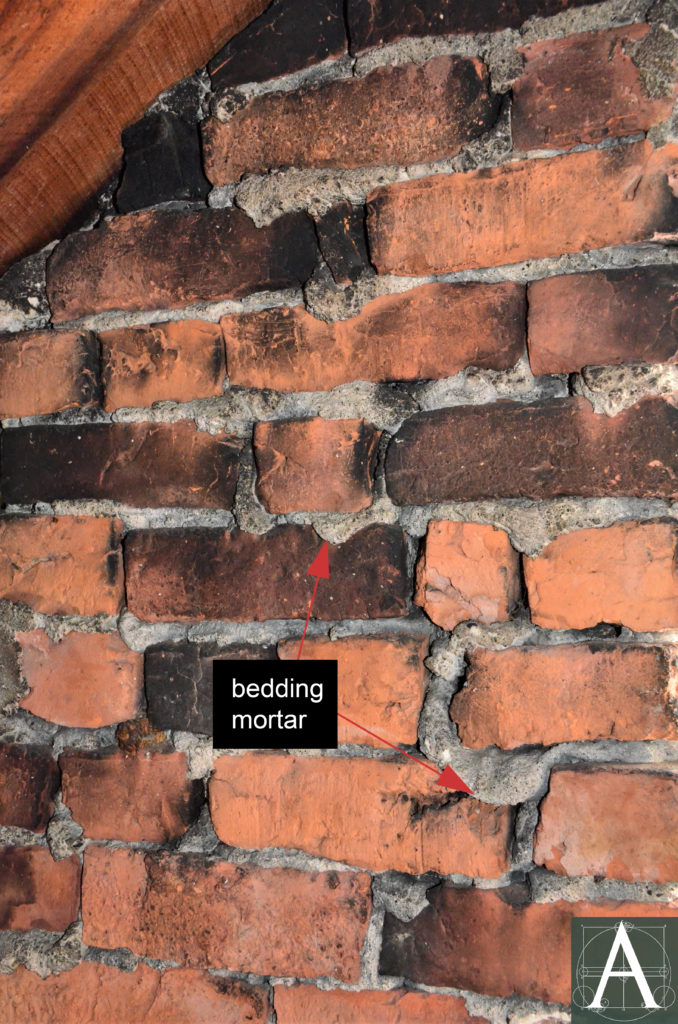

The rear (north) elevation retains some of the house’s most interesting evidence. Local tradition suggests that the wood-frame house of Leonard Weikes (Weeks) was incorporated into the Samuel Weeks House as a rear ell. In general, houses of this period had rectangular floor plans without the ells and wings that became ubiquitous in the first half of the nineteenth century. Evidence in the masonry suggests that the house did have a wood-frame rear ell and that it was, perhaps, in position while the house was being constructed. Scars from former roofing mark the gable of the rear ell on the north wall. In the area once sheltered by the ell’s roof, mortar in the belt course has neither been pressed back or tooled, as it is everywhere else on the exterior. Pressing back serves to compact lime mortar to make it dense and to eliminate voids, while the simple tooled lines applied to all other joints give the building a neat appearance and remove excess mortar from brick faces. The way in which bedding mortar has been squeezed through joints and allowed to cure in a curled position hanging out from the wall suggests that this area was concealed in a constricted roof space from the time of its construction and that the masons saw no need to finish the joints for exposure to the weather.

North and west elevations in the 1930s showing the scar of an original rear ell and rebuilt chimney caps [HABS, L. C. Durette, photographer]

North elevation close-up of original mortar applied in a wet state, never pressed back, and left untooled in a location concealed by an original rear ell

Mortar joints at the west gable of the attic match the appearance of joints in the location of the former ell. In both places, bedding mortar was applied in an unusually wet mix that squeezed out through joints creating the same appearance as plaster keys, although this excess mortar serves no beneficial purpose for masonry strength.

Close-up view of original mortar applied in a wet state, never pressed back, and left untooled at the interior of the attic’s west gable

One of the more puzzling aspects of the house is the question of whether part or all of it was intended to be coated, as was commonly done to protect soft-fired bricks from weather. Historic photographs are few, but early twentieth-century views show the house covered with a thick plaster and the chimneys covered by a thinner, somewhat uneven plaster. By the 1930s, the chimney caps had been rebuilt to a different design from their original configuration, and any evidence of plaster in that location was removed. Plaster on the building’s walls is shown in increasingly fragmentary condition throughout the early twentieth century until all of it had been removed except in the gables by the 1930s. Tradition indicates that the house was covered at one point with “cement” although that term once included a range of lime and other materials before Portland cement predominated in the twentieth century. The remnants of exterior plaster shown on historic photographs cover all elevations and appear unusually thick except at the old chimney caps; however, the chimneys within the attic are covered with similarly thick, flat coats of lime plaster to protect the clay mortar in which they were laid. Few installations of eighteenth-century exterior lime plaster survive in New England, but those that do make economical use of the material, applying it as a thin layer that appears somewhat uneven as it follows some of the irregularities of the base materials. Without samples of the Weeks House’s former exterior plaster, its period of installation cannot be confirmed.

Roof

Original roof coverings and evidence of them were lost in 1938 when a fire that burned the rear ell and barn also burned the roof. It is likely that the roof was originally covered with wood shingles.

Interior

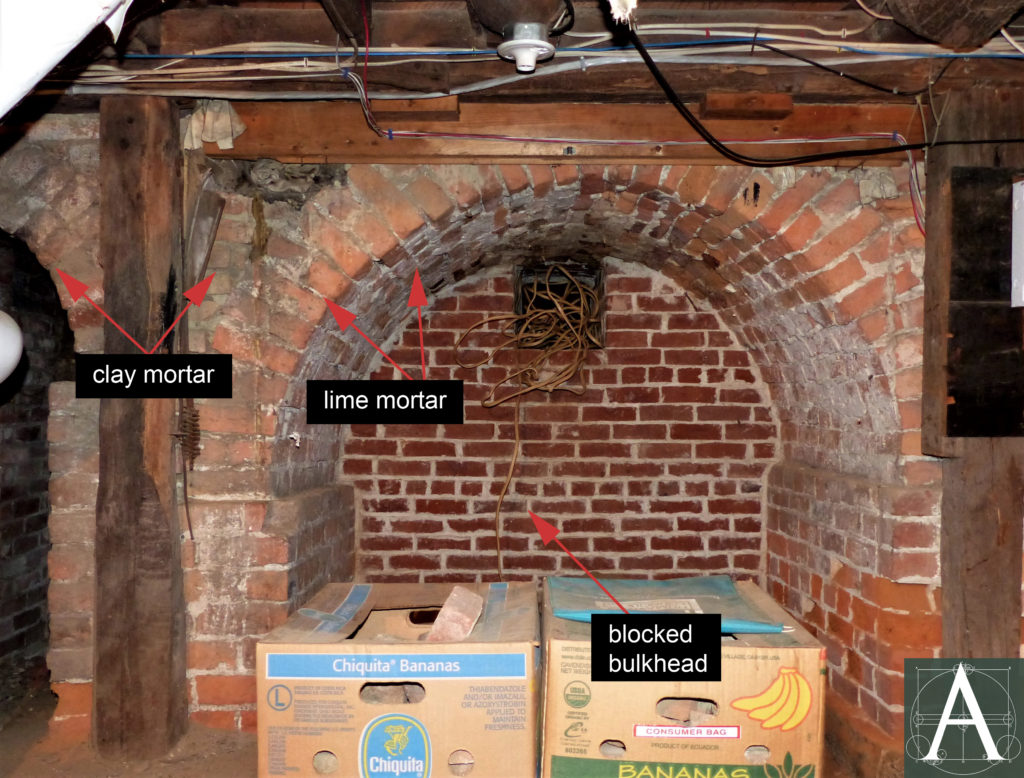

One of the major features of the house is its large kitchen fireplace at the east end of its first storey. Typical of kitchen hearths, the chimney rises from a base supported in the cellar by two broad arches, the southern one of which also served as a passageway from the exterior bulkhead. The northern arch was laid in clay mortar as was the spandrel between the two arches, while the southern arch was laid in lime mortar. It is not clear why these two arches should have had different mortars. These two mortars were commonly used in a selective manner for their different properties. Lime mortar was used for its strength at the arch and top courses of piers, and above the roofline where it was more resistant to weather, as it was as at the Matthew Perkins House (1701-09) in Ipswich, Massachusetts. Clay mortars were generally used in areas protected from weather and where they bore dead weight in compression, although they were used for both purposes at the Spencer-Peirce-Little House (1690) in Newbury, Massachusetts.

1930s view of the double-arched base of the kitchen hearth at the east end of the house’s cellar; the arch to the right also served as access to the exterior bulkhead [HABS, L.C. Durette, photographer]

View of the double-arched base of the kitchen hearth showing clay mortar installed at the arches’ spandrel and at the north arch; lime mortar installed at the piers and south arch (former bulkhead passageway, now blocked)

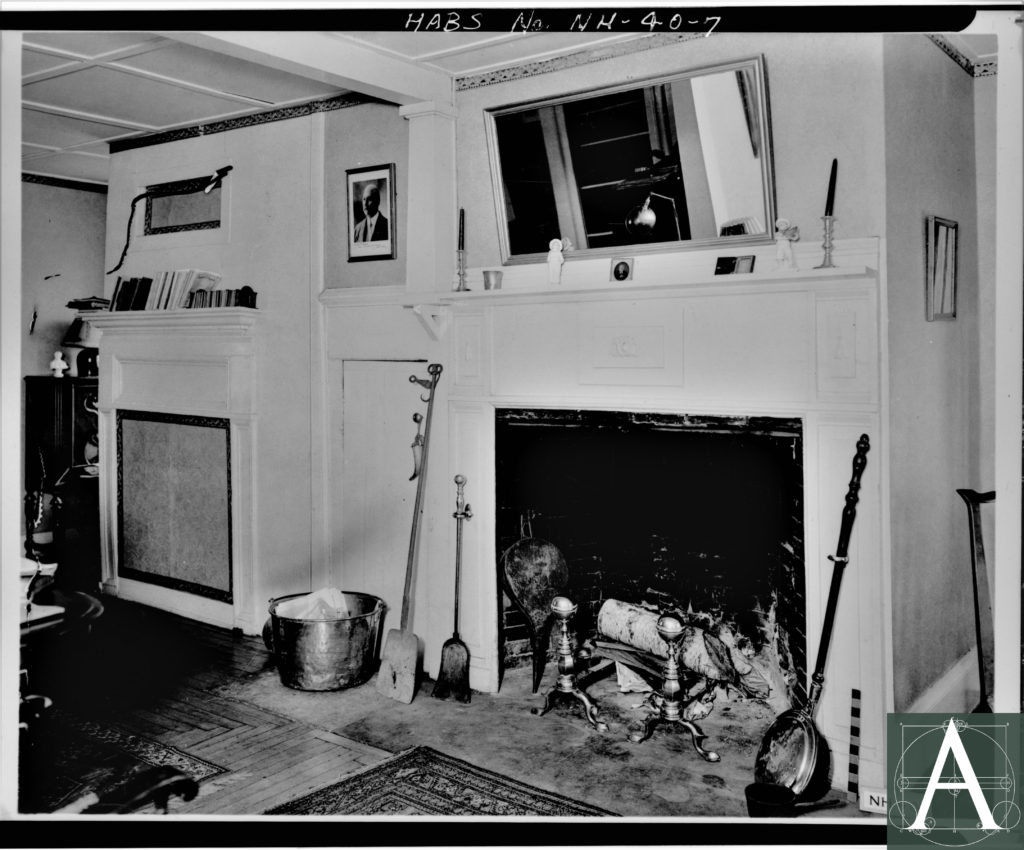

1930s view of later fireplaces (ca. 1830) built within the original kitchen fireplace (ca. 1710) at the east end of the first storey [HABS, L.C. Durette, photographer]

Partially reconstructed kitchen fireplace (ca. 1975-90?); fireback, oven, wooden lintel (chimney-tree), and portions of the south pier (right) and brickwork above the lintel appear original; other sections have been reconstructed

Interior view of the kitchen fireplace showing the roughly hewn bevel at the back of the oak lintel and surviving clay plaster on the chimney throat

Most of the interior finishes are simple, consisting of lime plaster at walls and ceilings, and paneled doors. Numerous small details of interest survive in the form of door hardware including wrought-iron hinges with foliate ends. Particularly rare details of the house are its several small closets where shaved wooden clothes pegs are mounted on boards fastened to the walls with hand wrought nails. Tucked in corners by chimney-breasts and in a back room, these closets bear eighteenth-century details that have generally been removed from similar storage spaces in other buildings of this period.

Early clothes pegs shaved to roughly hexagonal section set in base fastened with hand-wrought nails (pre-1800)

Contributor

Brian Pfeiffer, architectural historian

Sources

Historic American Buildings Survey: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/hh/item/nh0083/

http://www.weeksbrickhouse.org/

National Register of Historic Places Nomination https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/49832b75-2544-4272-91db-54ca63b6b907

New Haven Museum, Whitney Library manuscripts: J. Frederick Kelly, MSS-270.

Wikipedia: J. Frederick Kelly, architect. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J._Frederick_Kelly

Williams, George W. The Oldest House in New Hampshire. The Granite Monthly. XLIII:5 (Concord, New Hampshire; The Granite Monthly Company, 1910), 108. Online: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101066151836;view=1up;seq=123