Notable Elements

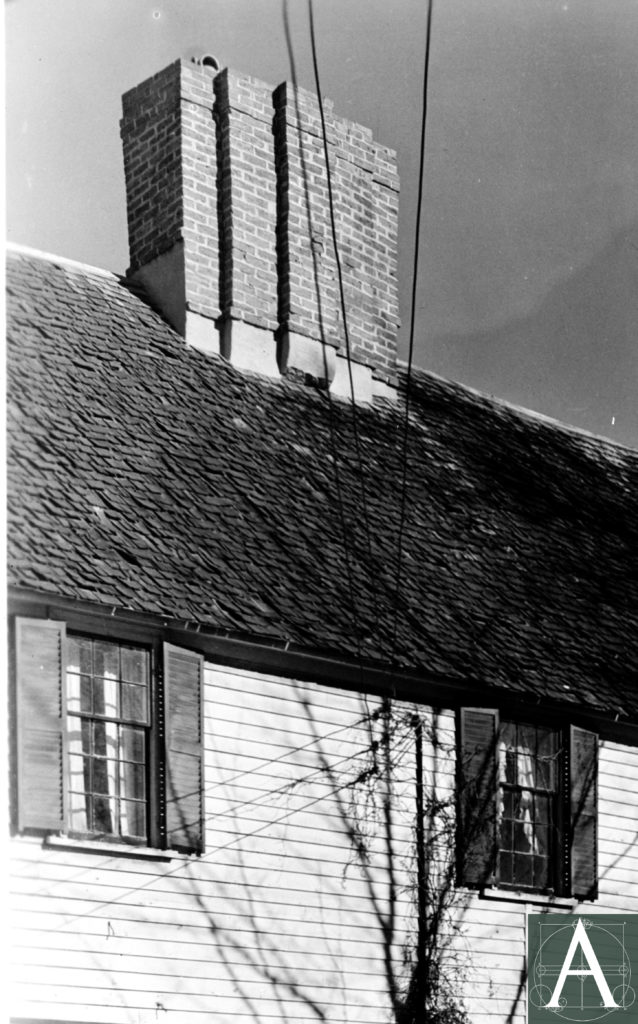

- massive central chimney laid in clay and lime with a pilastered cap [Interior]

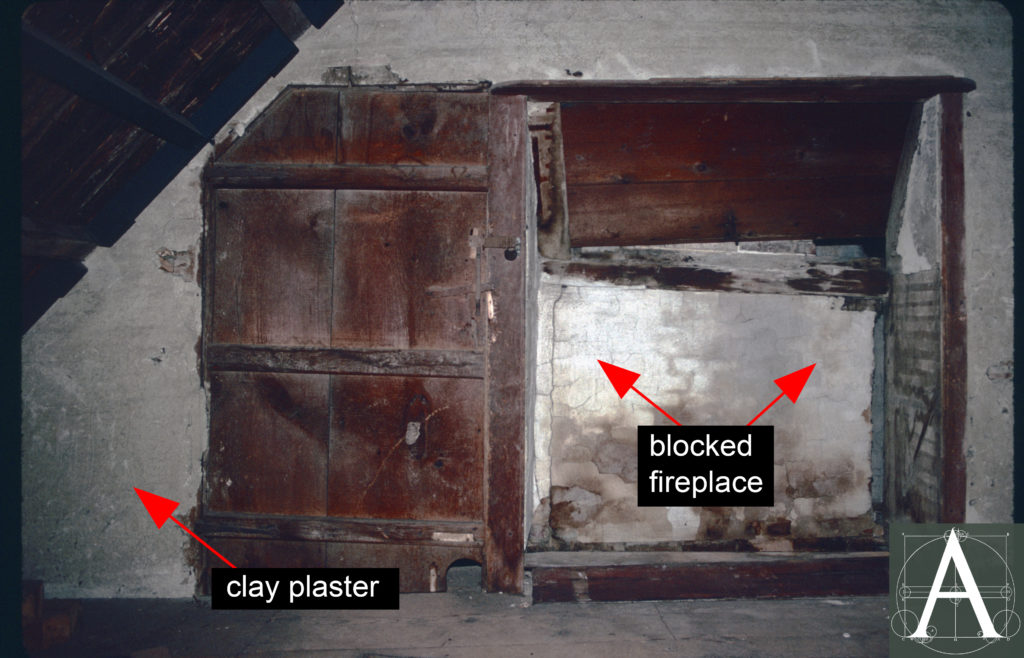

- clay plaster at interior (1st storey and attic) and clay daubing (cellar) [Interior]

- extensive evidence of casement window placement, dimensions and interior window finishes [Exterior]

- original timber frame with plank construction at 1st storey and two-storey corner & chimney posts [Frame]

History

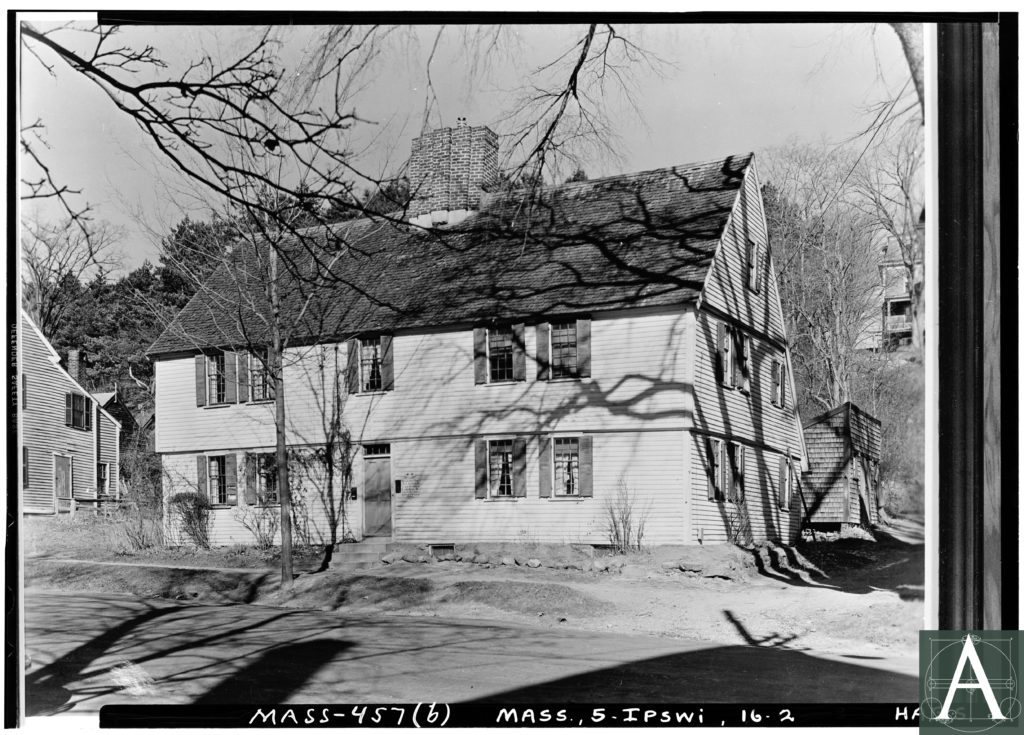

Constructed between 1701 and 1709, the Matthew Perkins House is a rare example of a substantial First Period house that has not undergone restoration. The building retains a high proportion of its original building materials (1701-09) as well as substantial elements from several periods of alteration (ca. 1750, ca. 1775-1800 & ca. 1840) that represent a characteristic pattern of divided ownership by which many New England houses evolved from single-family occupancy to occupancy by multiple generations of the same family and into the separate ownership of different parts of the building.

The house was built for Captain Matthew Perkins (1665-1738 – Perkins Genealogy), a weaver who was subsequently identified in public records after 1719 as an innholder and taverner. Following Perkins’ death, the house continued to be occupied by his widow, Esther, and, presumably, some of their children. Following Esther Perkins’ death in 1749, the house passed into divided ownership. One of the Perkins’ two daughters, Esther Harbin, inherited the western half of the house while the heirs of the other deceased daughter, Mary Perkins Smith, inherited the eastern half. Typically, the deed for this division ran through the centerline of the house: “by a line running southwasterly throw [through] ye Sd Dwelling House & Midl of ye chimney to ye Rode;…Also the seller [cellar] on the backside of the House with ye Arch together with ye privilege of passing and repassing throw the other part of sd seller.” (Essex County Registry of Deeds Docket #21382).

In 1752, presumably following the death of Esther Perkins Harbin, her half of the house was subdivided between her daughter, Esther Harbin Porter, and her youngest son, William Harbin. (Essex County Registry of Deeds Docket 21305). Esther Porter received “…the Lower Room & the Garritt Over it and the Easterly End of the Seller [cellar] twelve feett in lenth with ye liberty of passing through ye other part of sd seller”, while William Harbin received “…The Chamber & Linter chamber & the Back Room of said Manshon House with the other part of the Seller and the arch adjoining to it.” The eastern half of the house remained in single ownership, passing to Richard Sutton by 1762 whose widow in 1826 received “one full third part of said real estate as her dower…for her use and benefit during her natural life.” (Essex County Registry of Deeds Docket #26859). Sutton’s heirs sold the eastern half of the house in 1840 to Daniel Hodgkins, housewright, who may have made the last major round of modifications by installing lime plaster partitions and covering old sheathing with plaster. (Unrecorded manuscript, Ipswich Public Library).

The house remained in divided ownership until 1944 when both halves were acquired by Charles and Dorothy Pickard who owned the house until selling it to the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (SPNEA, now Historic New England) in 1966. In 1988-90, SPNEA undertook repairs to the building’s frame and chimney preparatory to selling the property into private ownership subject to permanent preservation restrictions.

Dates

1701-09; alterations ca. 1750, ca. 1775-1800 & ca. 1840

Builder/Architect

Unknown

Building Type

Central-chimney, timber-frame house with integral lean-to

Foundation

The majority of the building is set on dry-laid fieldstone frost walls concealing shallow crawl spaces in which many of the joists rested directly on soil. Only the southeast quarter of the structure has a cellar; its walls are dry-laid fieldstone daubed with clay mortar. At the east end of the façade, the foundation wall is capped with a brick wall above grade. Scars in the brick and notches on the front sill confirm the presence of an early, if not original, bulkhead which is also mentioned in deeds as early as 1762 as “outside cellar doors.” This bulkhead was removed and blocked during the nineteenth century.

Excepting the central chimney, masonry is limited to a dry-laid frost wall on which sills rest. The only variation in this condition exists at the southeast corner where a cellar is framed by fieldstone walls capped above grade at the façade (south elevation) with a brick wall. Internal faces of the stonework are daubed with clay, while the brick portions of the wall are laid in lime mortar. Evidence of a bulkhead remains in notches in the south sill, 8’-10” north of the building’s southeast corner. The notches indicate wooden posts that framed the cellar door, which had a clear span of 4’-1½.” Mentioned in a deed as early as 1768 (Essex Deeds, Book 121, page 253), the bulkhead entry to the cellar may have been an original feature of the house. This bulkhead was closed and replaced by an added bulkhead on the east elevation prior to 1936.

Frame

With an overall dimension of 48’ x 32’, the frame of the Perkins House is large for its period and was constructed in one campaign. The first storey is plank-framed while the second storey and gable ends are stud-framed. Corner posts at the southeast and southwest corners rise from 10” x 10” bases at the first storey to 12” x 12” at the second; the southwest corner post appears to be made from a single timber; the southeast corner post was not sufficiently exposed during repairs to examine its full height. All framing timbers are of oak with the exception of the second-storey girt, which appears to be made of white pine. This girt has a moulded face at the exterior overhang and a 2” x 2 3/8” deep rabbet on its underside to receive first-storey planks. The rabbet retains traces of the point marks of augers (approximately 4” on center) that were used to drill holes from which the channel was then chiseled to its present dimensions.

The roof is supported by a principal rafter and common purlin frame. The small dimensions of the roof frame tested the limits of how lightly such a structure could be framed and required supplemental stiffening in the late twentieth century.

Repairs conducted by David Webb of Newbury, Massachusetts, in 1988 consisted of excavating the rear (north) wall of the house where original sills and the lower portions of wall framing had rotted and been replaced by a poured concrete base (ca. 1940-50). In addition, the rear wall had been largely re-framed and fitted with new windows and two small entry porches, all of which were removed to conduct structural repairs. Subsequent framing and fenestration represent contemporary repairs and do not restore earlier conditions for which no evidence survives.

Additional repairs conducted by the Warwick Carpenters’ Company of Warwick, Massachusetts, consisted of repairing rotted sills and corner posts at the south, east and west elevations of the front part of the house by splicing new members into sound original elements.

Exterior

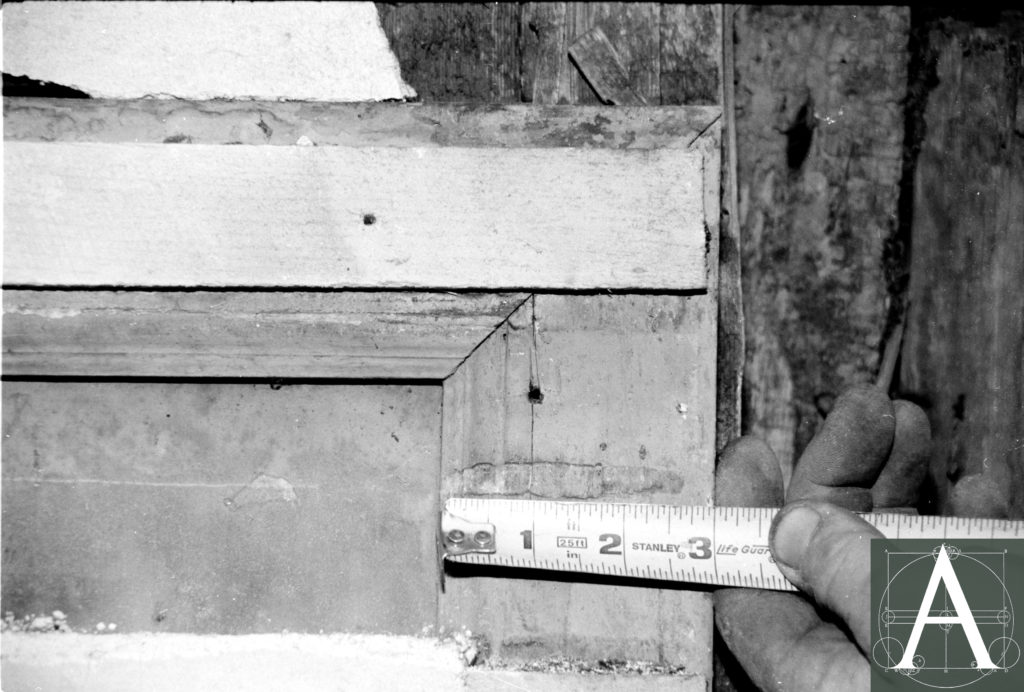

Windows: Although all remaining windows are double-hung sash dating from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the house preserves extensive evidence of original casement windows. The most substantial evidence was found in the east wall during sill repairs. At a point near the center line of the southeast room, partial height studs were found at points 85½” and 143” north from the southeast corner post. With a clear span between them of 54-1/2”, these studs bore mortises for a window sill at a height of 36” above original floor level. Buried in the wall between the two studs was a section of paneling with original moulding profiles and corresponding in height to the space beneath the mortises. The one surviving complete panel is 12-7/8” wide set in stiles 3” wide. Extending these dimensions to three panels set in four stiles (as would be found beneath a window) yields an overall dimension that nearly matches the clear span between window studs. This condition strongly suggests a triple casement window in this location.

The west wall bears substantially the same evidence of window studs and sill heights (37-1/2” above floor level) at the first storey, as well as window studs directly above at the second. At the west end of the façade, second-storey framing also includes original window studs with a clear span between them of 57-1/2” set 77” south of the northwest corner post. Inconclusive evidence east of the main entry suggested that there may have been two different casements of narrower dimensions providing light to the first storey east room; the second storey wall of the east chamber may retain evidence of original windows, but it was not opened as part of the 1988-90 repairs.

Original panel from east wall covered by layer of plaster on sawn lath, ca. 1840 (image courtesy of Historic New England)

Detail of stile and moulding at original panel from east wall (image courtesy of Historic New England)

Detail of original paneling beneath casement window at east wall after partial removal of ca. 1840 lime plaster and sawn lath (image courtesy of Historic New England)

Roof

Steeply pitched gable roof with integral lean-to at rear (north) slope; no evidence of gables or dormers. Historic photographs show the roof covered with wood shingles, which seem likely to have been the material with which the roof was originally covered.

Interior

Interior Wall Finishes: Although much of the house’s interior was plastered, perhaps in the 1840s, substantial areas of original sheathing, paneling and clay plaster remain; these are:

- 1st storey east of chimney: The large east bay is divided internally into three rooms, an arrangement that was commonly practiced with sheathing partitions in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; however, current partitions appear to be stud and plaster. The fireplace wall retains raised paneling from the mid-eighteenth century and the east wall of the southeast chamber retains an original wainscot panel that has been returned to the position in which it was found.

- 1st storey entry/stair hall: The front staircase is a rare surviving First Period staircase of unusually broad dimension occupying the full width of the house’s 10’ wide central chimney bay (Cummings, p. 165); it retains its sheathing, shadow mouldings and turned balusters. Fragments of clay plaster with animal hair added for tensile strength remain at the face of the chimney in the cellar way.

- 1st storey west room: The fireplace wall retains a mixture of original sheathing at its doorway, added raised paneling over the fireplace (18th century) and an added mantel shelf (ca. 1800-20). The room’s walls were plastered in the first half of the nineteenth century at which time the summer beam had its lower 2” chiseled away and corner posts and their corners chiseled back to allow plaster to create a fully square room without the projection of framing timbers into it.

- Attic: a wall of clay plaster survives at the east face of the chimney together with fragments of clay plaster on riven lath on the east gable.

Fragment of clay plaster with animal hair for tensile strength at 1st storey (image courtesy of Historic New England)

East half of attic showing blocked fireplace, batten door and wall of clay plaster (image courtesy of Historic New England)

Detail of attic chamber wall showing blocked fireplace with slipped lintel, batten door and clay plaster (image courtesy of Historic New England)

Hardware: Extensive hand wrought hinges and latches survive in the house but have not been inventoried.

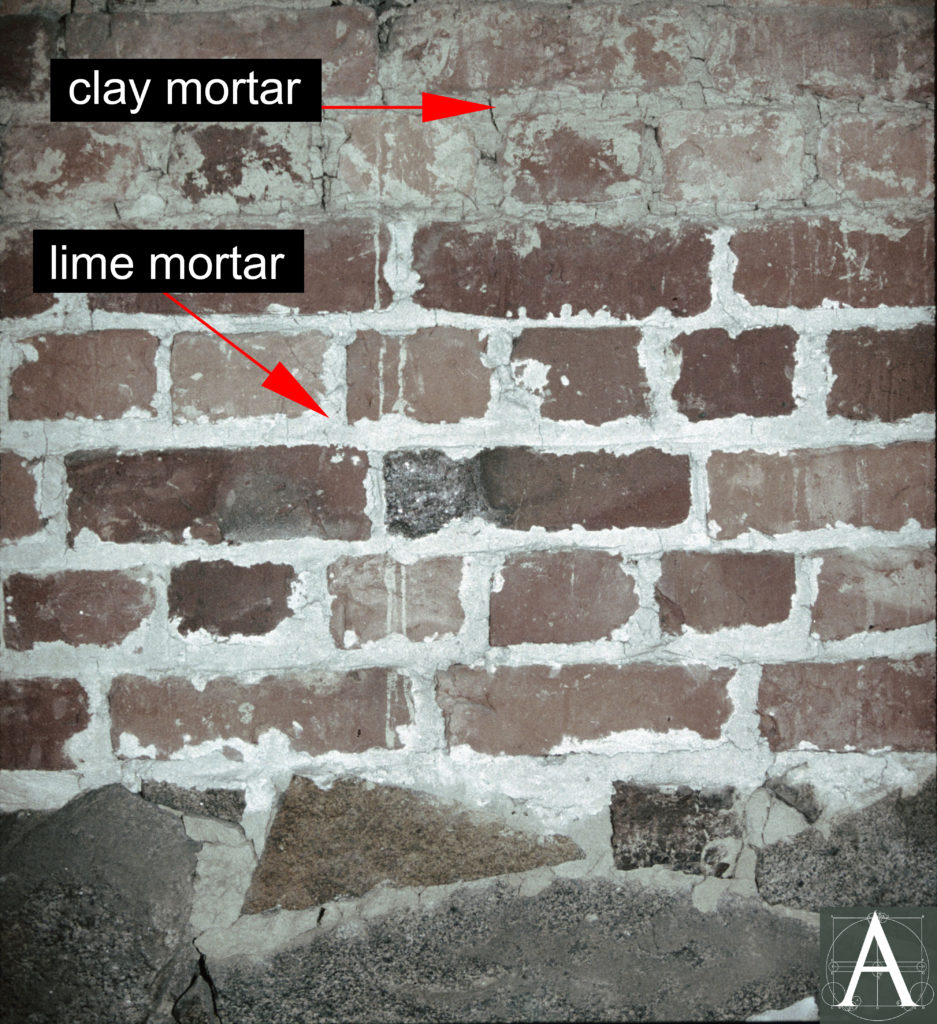

Central chimney: The central chimney is unusually massive and occupies a wide chimney bay slightly north of the façade’s center. The western half of the chimney rests on grade, while the eastern half stands within the cellar and is supported by two dry laid stone piers pointed with lime mortar that rise to a brick arch. The lower five to seven courses of the brick piers and arch are laid in lime mortar after which the stack is laid in clay mortar to a point just below the roof’s ridge where a surviving course of lime mortar with visible shell fragments remained in position (1989) despite the replacement of the original cap above the roof line. Exposed brickwork in original fireboxes was also pointed with lime mortar.

Base of central chimney showing stone piers and supporting arch laid in lime mortar (image courtesy of Historic New England)

South wall of central chimney showing top of stone pier, five courses of brick laid in lime mortar surmounted by brick laid in clay mortar (image courtesy of Historic New England)

The first storey of the chimney contains three fireplaces, namely back-to-back fireplaces serving the east and west rooms and a large cooking hearth facing north into the lean-to. A similar arrangement of back-to-back fireplaces remains at the east and west chambers of the second storey, although there is no firebox at the second storey. The east face of the chimney at the third storey preserves a rare attic fireplace that may have been original to the building or a very early alteration.

All fireplaces were filled with smaller fireboxes in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, leaving original fireboxes in position. At the east and west rooms of the first and second storeys, all new fireboxes were accompanied by domed brick bake ovens on their north sides. The former kitchen hearth at the first storey was subdivided in the eighteenth century by a partition running through its center and two angled fireboxes were added facing northeastward and southeastward.

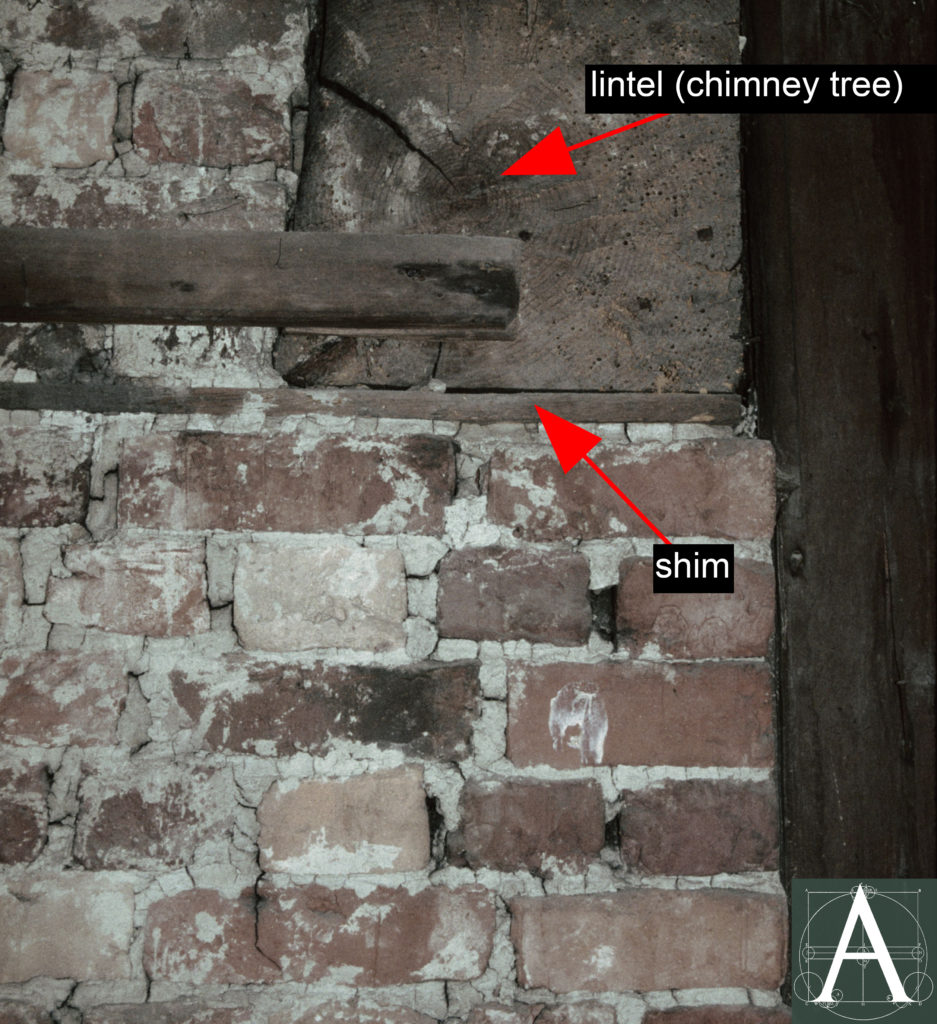

Knowledge of original fireplaces was gained during repairs conducted in 1989-90 and is limited to those areas opened up by repairs to the later fireboxes. At the first storey, original fireplaces were supported on oak lintels set on sleepers. Masonry hoods above the lintels were strengthened by single brick arches set 7’-2” above the hearths and extending from the hoods to the masonry back walls of the chimney throats. Evidence for original bake ovens remains in the form of angled corner walls: the southwest corner of the east fireplace and the northeast corner of the west fireplace where a patch in the brickwork (9” high x 8” wide) may enclose a former oven door. At the second storey, east and west fireplaces were broad open fireboxes with curved corners. Brickwork was laid in common bond while curved corners were laid with headers.

One wooden pole (trammel bar) was found in the throat of each of the original front fireplaces. These bars were hexagonal and set between 79” and 82” above the hearths and between 14” and 18” distant from the jambs of the first-storey west fireplace and both second-storey fireplaces. The east fireplace of the first storey retained a burned fragment of such a pole set 73” above the hearth.

End view of chimney tree (lintel) bedded on a wooden sleeper set in brickwork with clay mortar at the south jamb of the east fireplace at the first storey (image courtesy of Historic New England)

Hexagonal wood trammel bar (1701-09) at the 2nd storey west chamber with clay/lime parging in background (image courtesy of Historic New England)

The original kitchen fireplace was concealed by two smaller fireplaces to serve the two halves of the house after it was divided into separate ownership in the eighteenth century. These fireplaces were built on hearths set on grade; as found in 1988, both were collapsing due to poor footings. In addition, the lintel of the original kitchen firebox had been cut in the eighteenth century and poorly supported. Portions of the original firebox were unstable and possibly collapsing. For these reasons, the two added fireboxes were measured, documented and removed, after which the surviving fragments of the original kitchen fireplace were stabilized and left in position. Too little evidence remained for accurate reconstruction, and conservation of original material was deemed preferable to conjectural reconstruction given the unrestored state of the house. Similarly, the attic fireplace was blocked and has been left in position to preserve its unrestored evidence.

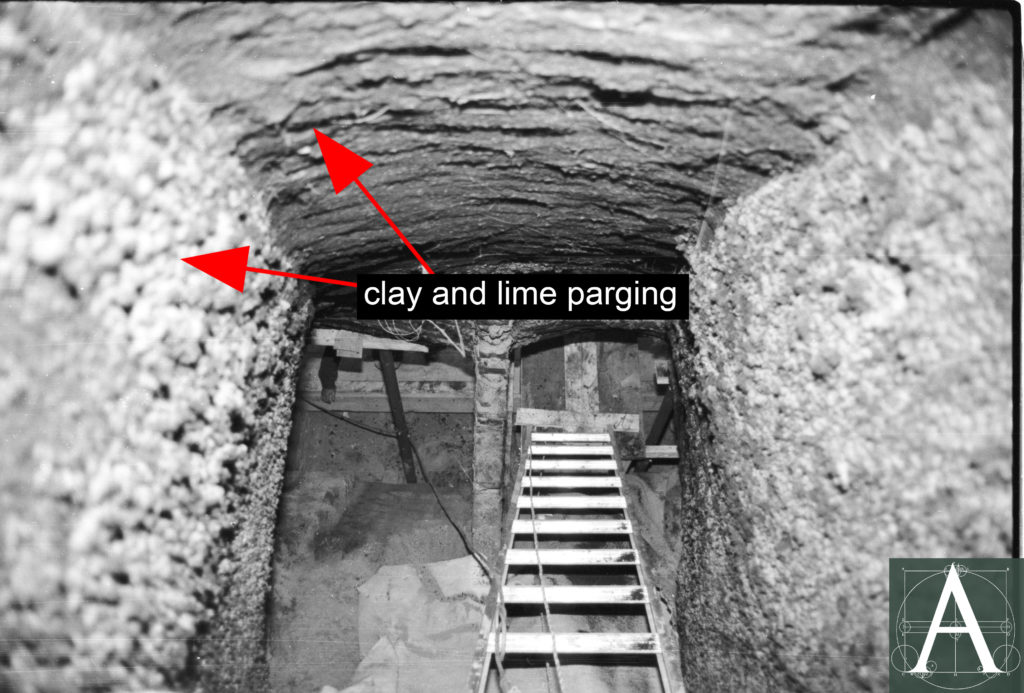

Chimney flues were lined (parged) with a mixture of clay and, perhaps, lime. This lining was retained and repaired to render the flues functional in repairs conducted in 1989-90.

Interior of rear (east) flue to the former kitchen fireplace, lined with clay/lime render (image courtesy of Historic New England)

All four front fireplaces were concealed in the eighteenth century with smaller, more efficient fireplaces and with domed brick bake ovens. This later infill has been left in position and remains the current condition of the building.

The chimney cap that had been rebuilt with tapestry brick after 1936 was reconstructed in 1989 to reproduce the pilastered chimney stack shown in nineteenth-century and 1936 documentary photographs of the building.

Contributor

Brian Pfeiffer, architectural historian

Sources

HABS – Matthew Perkins House (formerly Morton-Corbett House)

Massachusetts Historical Commission – Perkins House Inventory

Cummings, Abbott Lowell. The Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay, 1625-1725. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1979: 99, 100, 124, 126, 165 & 169.

Historic Structure Report: Matthew Perkins House. Anne Grady, et al. (unpublished, Historic New England, 1988).

Deed citations:

- Essex County Deeds, Book 121, page 253. Deed from Jonathan Newmarsh of Ipswich, fisherman, to Ephriam Kindall [sic.]

- Essex County Registry of Deeds Docket #21382 – 1749

- Essex County Registry of Deeds Docket 21305 – 1752

- Essex County Registry of Deeds Docket #26859 – 1826

- Unrecorded manuscript deed to Daniel Hodgkins – 1840 – Ipswich Public Library, Ipswich Room